image sonification and the study of the ephemeral past.

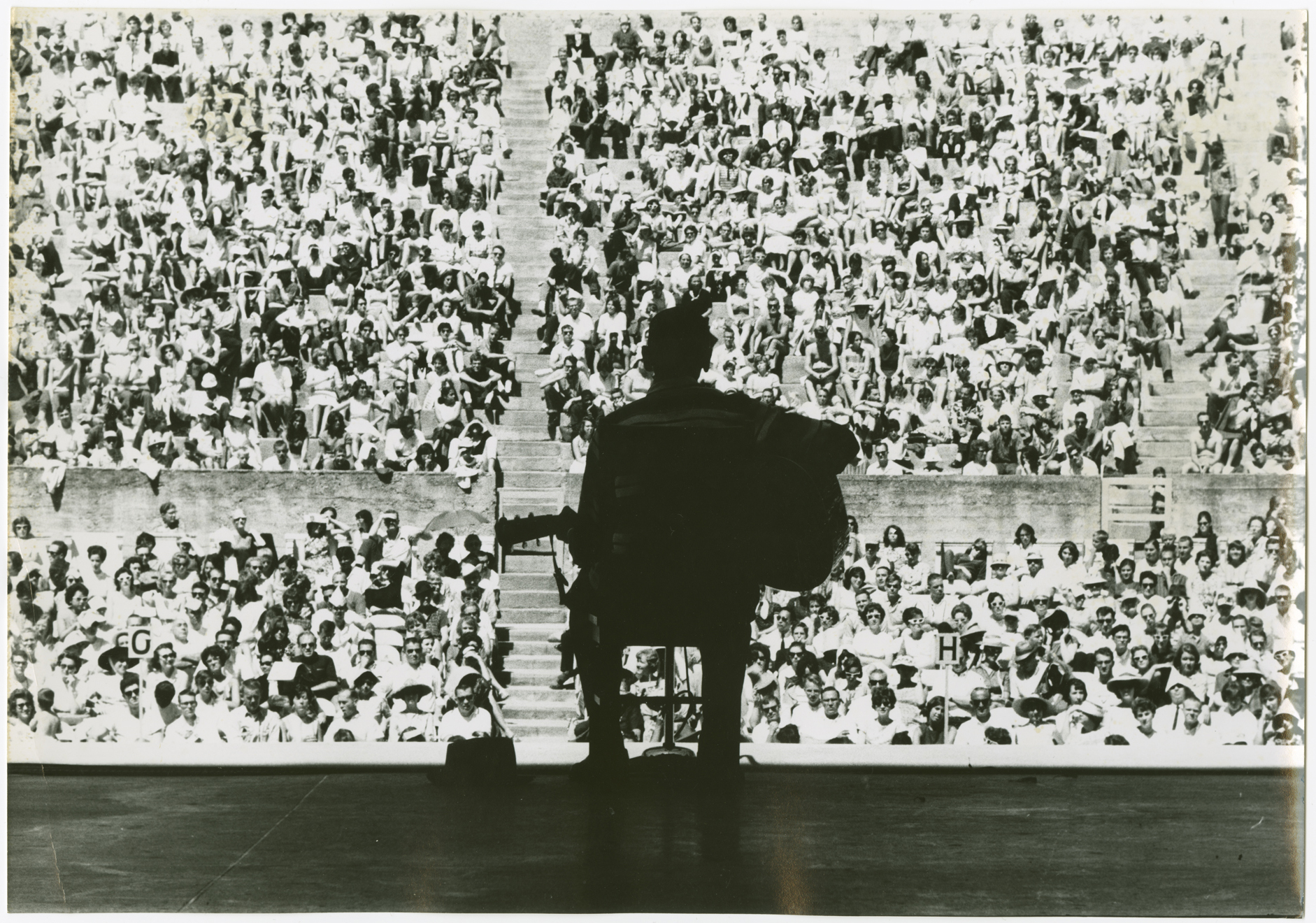

At the center of the photograph, in silhouette, sits Mance Lipscomb. Guitar across his lap, the African-American songster and lifelong sharecropper from Navasota, Texas plays the blues to a large audience at the University of California’s Greek Amphitheater. It is a sunny day in 1961 at the third annual Berkeley Folk Music Festival. It is also Lipscomb’s first big performance after being “rediscovered” one year earlier by two white folklorists, Mac McCormick and Chris Strachwitz. The image is itself silent, of course; symbolically, however, it speaks volumes. The size of the crowd, filling the 8,5000 seat amphitheater, reminds us of the popularity of folk music during the early 1960s. The setting of the Greek Theater indicates the interest in the United States in linking its institutions of higher learning to antiquity, particularly Athens, the so-called birthplace of democracy. Lipscomb’s presence, moved from obscurity at the margins of US society to a stage at one of the crown jewels of the nation’s system of public higher education, registers the cultural dimensions of the burgeoning modern African-American civil rights movement. The interplay of the lone figure playing acoustic and the presence of the microphone next to him suggests the many technological mediations at play in the folk revival. So too does the photograph itself, which is but a visual representation of what was at its core a fundamentally noisy event, filled with musical and aural experiences. People came, after all, primarily to hear Lipscomb at Berkeley.

My current book project, The Garden in the Machine: Folk Music and Technology, also seeks to hear Lipscomb better. It does so by applying digital techniques to powerful images such as this one in order to analyze them in new ways. The larger research project is multimodal: exploring the unexpected engagements with life in a modern technological society within the ostensibly antimodernist, anti-technological culture of the folk revival, it includes a book monograph, a traveling exhibition of materials from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection (from which the Lipscomb image comes), and an interoperable digital archive that includes a suite of analytic tools for the study of vernacular music and culture by scholars, educators, students, musicians, artists, and the general public. In the coming years, I will be focusing on the concept of “image sonification” as part of my research. In this work, I ask whether computational power and the convergence of visual and sonic media as data offer new opportunities for thinking aurally as well as visually about the past, particularly about ephemeral but influential experiences such as musical performance at gatherings such as the Berkeley Folk Music Festival. I ask whether we can listen to images as well as look at them? What would it mean to ask the question “what does an image sound like”? Can we sonify images in productive ways to reveal what they contain about the “audible past,” even if it is buried in their visual data? Can we even amplify these aspects of the visual by using our ears as well as our eyes? Most of all, can a pivoting between the visual and audio, between sight and sound, enable unexpected perceptual and haptic experiences of historical “data” that in turn undergird new ways of knowing the past, particularly the ephemeral past of aurality and its historical significance? My hypothesis is that because they allow us to transit between data outputs and the senses we use to process these digital re-representations of the past, computational and multimedia technologies have the potential to give voice to the “silences of the archive” in ways that the “analog” archive could not. At a level removed from the actual events, they have the paradoxical capacity to bring us one step closer to them.

The image of Lipscomb comes from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection. A 30,000-plus object archive that is housed in the Special Collections Library at Northwestern University, the Berkeley materials document an annual event that occurred on the University of California campus from 1958 to 1970. A number of audio recordings from the festival exist, but the most astounding part of the Berkeley Collection is its rich trove of photographs, roughly 10,000 images that present wide-ranging snapshots of performers and audiences as well as the built environment in which the folk festival took place (quite literally the same spaces as much of the political protest on the Berkeley campus during the 1960s). These images, digitized, provide an ideal test bed for investigating how we can use digital-based, multimedia technologies to think through sound in innovative ways. We cannot, of course, recover the actual sounds being made in the photographs (at least not yet!), but through innovative digital means we can turn our attention to the sensorial experiences and perceptions of past sounds as they are embedded in visual data. We can pair visual extraction techniques (shape extraction, color saturation measurements, hectograms, facial recognition programs, depth and spatial relationships, vectorization) to sound synthesis strategies (pitch, rhythm, meter, volume, timbre, sampled sound designs). These correlations create sound compositions that can spark new perceptions of images, which in turn can inspire new interpretations of the past. They return the spatial data of images back to the temporal qualities of music by allowing users to transit between the two in search of undiscerned patterns, levels of intensity, frequency of a particular instrument or performer, and other qualities held within these visual representations of the ephemeral past. One might, for example, be able to extract where audiences are looking in a series of performance images, then sonify these to register intensity of attention and better understand the “charisma” of a performer. One might probe an image’s formal qualities and sonify them to see relational details that the eye did not at first glimpse. One might even “scale up” from microanalysis of one image to the “big data” processing of thousands of images to measure and communicate information across the corpus of Berkeley photographs: average crowd sizes, most-commonly used instruments, or typical postures of performers can be measured visually and then heard most evocatively in sonic form.

To investigate what correlations of image and sound are productive, however, requires iterative experimentation as I and others develop an open-source, user-friendly architecture and tool for image sonification. It requires thinking about research that is not only multimedia in nature, but also multi-sensory, expanding the repertoire of what “counts” as historical evidence, theory, argument, correlation, causality, speculation, and knowledge. While many contemporary digital humanities scholars currently focus on visualization studies, I want to shift our attention to another sense organ: the ear. It remains underutilized as a perceptual entrance into analytic study, but with the digital, the movement from image to sound and back again to image can extend the repertoire of humanistic inquiry. To give as much attention to the aural as the visual, the auricular as well as the optic, can enrich our understanding of the particular topic of technology and culture in the US folk music revival. More broadly, it reveals how digital technologies open up new avenues of understanding, meaning-making, and insound as well as insight.

Really cool, Michael. Being a rank amateur at what you’re doing, I don’t have particular knowledge of the questions, but it seems to me you’re asking good ones. To put yours another way: What, in a photograph (or other artifact traditionalky apprehended visually), is data? Then how can that data be represented in other forms to tell us more? Plenty of public humanities approaches so far have gestured at what you’re doing, by putting approximations of audio that was present at the time of a photo with the photo in an exhibition (museum, documentary, etc) including a photo, but I haven’t ever seen something that dealt with the photo’s visual content in this way. But also, as you’re doing, we can’t use (perhaps) the data from the photo as a physical object (metadata, really) and we’ve got to get beyond visual data as being the colors/tones/hues/etc of the object. I look forward to hearing where this goes. (“Insound” — wonderful!)

Hi Trip —

Being a rank amateur is just the thing to be when it comes to the folk revival (and maybe as well to digital technology!). I love the way you frame the question here around data. Yes! This word—data—carrying so much weight right now culturally, intellectually, dare I say even politically—requires a lot more investigation and careful scrutiny. In this project, in a bit more zany and off-kilter way I am building here on Fred Gibbs and Trevor Owens groundbreaking work about what they call “The Hermeneutics of Data and Historical Writing” (http://writinghistory.trincoll.edu/data/gibbs-owens-2012-spring/). My addition is to draw on the “deformance” approach of media artists, lit folks, and a few scattered historians to pursue artistic composition in service of analytic historicization. If all my artist friends now pursue “research” in the making of their art, should not we humanities researchers pursue “art” in the making of our research!

Really what you are noticing is something I have pondered too: what is the “material” reality of the digital? Historians have only begun, I think, to grapple with this question. Digital surrogates of “analog” materials particularly raise this question. How do we think of this “stuff” not just as a straightforward re-mediation of older modes of representation such as the photograph (or the word or the document for that matter), but as something that opens up new opportunities in its very re-mediation?

Calling a photograph data, as you do, forces us to think with more care and precision (and a healthy dose of adventurous weirdness) about what data is exactly, both epistemologically and phenomenologically, even ontologically and certainly materially. How are historians and humanities scholars going to approach data, use it, make sense of it, for making meaning out of new kinds of artifactual evidence that can serve as a basis for understanding the past. What can we do with the enhanced plasticity and malleability of digitized artifacts—the evidence of the past as data, and not just data as numbers and statistics, but data as in code, bits, bytes, software, hardware, etc. as the very stuff that represents human culture increasingly? Thanks. Do stay in touch of course!

–Best,

Michael