modernism as the folk art of modernity?

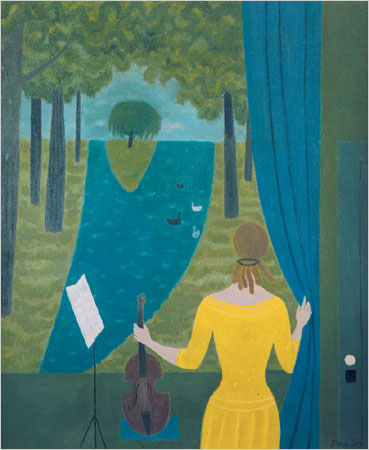

Last post (“The Mod Look in Folk Art”), I asked if a folk artist was merely a modernist with a good marketing plan? Today, in a kind of follow-up review in the New York Times by Roberta Smith, the art of Doris Lee posed a corollary question: is a modernist merely a folk artist responding to a new folk milieu?

If not, is there something about the distance, the remove, the consciousness, the purposefulness, the premeditation, the irony of modernism that distinguishes it from folk art, which we use to define (probably dubiously) art that seems unmediated, direct, without irony? Let’s say that the new context for art in the twentieth century involved a new kind of authenticity for the ironic perspective on life—an irony wrought by industrialization, bureaucratization, centralization and their alienations and absurdities (earlier phases of society had their own alienations and absurdities of course, but not the same ones). If folk art is art grounded in everyday life, and modernization transforms everyday life, then modernism is a kind of folk art for its times.

Maybe these labels and the debates about them are just silly. But we use those terms, so we should think about them carefully. More significantly, we feel aesthetic responses of authenticity and irony to the art that we have to name and label, even if those names and labels are misleading and, ultimately, contradictory. So probing those responses to art for their social embeddedness is worthwhile.

Folk artist, modernist. They signal different social positions, different populations, different markets, different milieus, but the dialectic between them fuses in the story of modernity itself and its all-pervasive transformations of perception.