fall 2020 @ suny brockport.

Welcome to HST 390 Historical Research Methods: Music & History

In Historical Research Methods: Music and History, you have an opportunity to develop your historical research, analysis, writing, oral presentation, and digital skills. We will focus especially on how to more effectively interpret non-textual sources (images, music, sound, built environments, material culture, numerical data) as well as textual documents in order to craft evidence-based arguments about the past. If you work diligently in the course, you will not only emerge a better historian, but also better equipped for any kind of research, analysis, writing, and communication you will do in a future professional career or in your life as a citizen and a person.

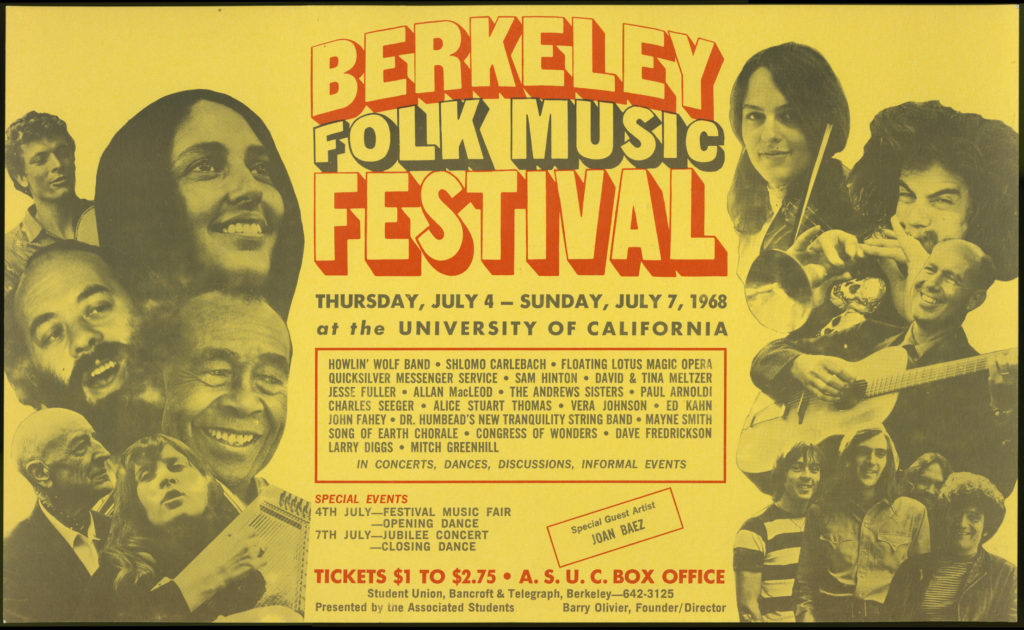

For the seminar, we use artifacts and stories from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project (BFMF.net) which is a public history effort directed by Professor Kramer. Each student will connect a particular story (and particular archival sources) from the Festival’s digital archive to a specific historiographic debate as well as to additional primary source/archival material. The Berkeley archive contains over 40,000 objects pertaining to a folk music festival that took place annually on the campus of the University of California-Berkeley between 1958 and 1970. It is chock full of amazing historical artifacts, many barely, or even never, seen or heard before.

By engaging wholeheartedly with the material in this course:

- You’ll become a better researcher, thinker, writer, and speaker.

- You’ll be able to handle complexity of evidence and organize facts into a narrative with an argument.

- You’ll be able to convey your evidence-based interpretations more compellingly whatever career you go in as well as in your personal life and in your role as a citizen.

So let’s dive in.

What You Will Learn

This course is modeled after the classic history research seminar imported from German universities to the United States in the late nineteenth century. The seminar is an opportunity to work together on how we think about and analyze historical topics, with ample opportunity for reflection, discussion, oral presentation, written analysis, and collective inquiry.

Over the course of the semester, you will:

- develop your ability to gain a general understanding of a particular historical context, in this case the decades in the United States and the world after World War II.

- improve your ability to wield critical concepts of interpretation such as identity, power, race, ethnicity, gender, class, region, structure, agency, representation, private, public, and other key analytic terms.

- practice your ability to write a historiographic essay that describes, compares, and draws conclusions about prior historical interpretations in conversation with each other.

- develop the capacity to frame an effective historical question.

- work on skills of close reading of evidence, development of a thesis/argument, and outlining, drafting, and revising a polished piece of historical writing.

- learn how to use source citation using Chicago Manual of Style effectively and accurately.

- complete a compelling, evidence-based, argument-driven essay based on original historical research.

- improve skills of oral presentation and communication.

- explore possibilities of digital platforms for presenting and analyzing historical material.

How This Course Works

This is a hybrid online course.

It is partly asynchronous and self-directed. You will complete assignments and digest readings, lectures, and other materials on your own, independently, following the deadlines listed on the course website.

It is partly synchronous, with required discussion sessions using the Collaborate tool through Blackboard (which is very similar to Zoom). These will take place mostly during our Wednesday scheduled meeting time, which is 10:10-11am. These are required. Sometimes we will talk as a group, sometimes we will break out into smaller discussion groups.

HST 390 Fall 2020 edition uses a number of digital tools:

- You may have noticed that I use Canvas instead of Blackboard because I think it is slightly better designed. It’s not perfect, but more pleasant to look at and navigate and use as both an instructor and, I think, as a student (I’ll be curious to hear what you think at the end of the semester).

- We also use online software such as VoiceThread (for, among other things, a recorded oral presentation you will prepare about your research project), Kaltura Media (for films to view), Collaborate (for synchronous discussion), MS Word (which you can download for free through Brockport On the Hub), and Google Docs (which you can create a free account to use).

- We will also use WordPress as a place to compile ancillary digital material that accompanies your final interpretive, evidence-based essay in the course.

- You’ll need a computer, of course, to be able to use material in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository and other digital repositories and materials. A laptop or desktop is preferable to a smartphone or tablet.

If you have questions about the technical details of the course, or about the hybrid nature of the course, please feel free to contact me.

Who Is Your Professor?

Dr. Michael Kramer

Assistant Professor, Department of History Department, SUNY Brockport

Office hours: Remotely, by appointment

Email: mkramer@brockport.edu

Bio: Michael J. Kramer is an assistant professor in the Department of History at SUNY Brockport. He specializes in modern US cultural and intellectual history, transnational history, and public and digital history. He is the author of The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (Oxford University Press, 2013) and is currently writing a book about technology and tradition in the US folk music movement, This Machine Kills Fascists: What the Folk Music Revival Can Teach Us About the Digital Age. He is also at work on a digital public history project about the Berkeley Folk Music Festival and the Sixties Folk Music Revival on the US West Coast. In addition to experience as an editor, museum professional, and dance dramaturg, he has written numerous essays and articles for publications such as the New York Times, Washington Post, Salon, First of the Month, The National Memo, The Point, Theater, Newsday, and US Intellectual History Book Reviews. Kramer blogs at Culture Rover and Issues in Digital History. More information about his research, teaching, and public scholarship can be found at his website, michaeljkramer.net.

More about what I research and teach in modern US intellectual and cultural history.

More about the SUNY Brockport History Department.

What Makes for Good Work?

Rubric

There is a craft to historical interpretation. The assignments will help you approach this craft and continue to improve your practice of it. Your task in each assignment is to develop effective, compelling, evidence-driven arguments informed by historical awareness and thinking. These will often work by applying your judgment and assessment to consider how things connect or contrast to each other: how do different or similar artifacts, documents, quotations, details, facts, and perspectives relate to each other? And most importantly, why? What are the implicit ideas and beliefs behind the evidence you locate and analyze?

Aspire to make your assignments communicate a convincing, compelling, and precise argument. The argument, to succeed, should display close analysis of details found in the evidence. These should be contextualized effectively: what else was happening at the time? How does the evidence relate to the broader framework of its historical moment?

Try to write, edit, and revise to achieve clarity of expression in graceful, stylish, logical, well- reasoned prose. Evaluation of assignments will be based on the following rubric:

- Argument – presence of an articulated argument that makes an evidence-based claim and expresses the significance of that claim .

- Evidence – presence of specific evidence from primary sources to support the argument.

- Argumentation – presence of convincingly connection between evidence and argument, which is to say effective explanation of the evidence that links its details to the larger argument and its sub-arguments with logic and precision.

- Contextualization – presence of contextualization, which is to say an accurate portrayal of historical contexts in which evidence appeared.

- Style – presence of logical flow of reasoning and grace of prose, including:

- (a) an effective introduction that hooks the reader with originality and states the argument of the assignment and its significance

- (b) clear topic sentences that provide sub-arguments and their significance in relation to the overall argument.

- (c) effective transitions between paragraphs

- (d) a compelling conclusion that restates argument and adds a final point

- (e) accurate phrasing and word choice

- (f) use of active rather than passive voice sentence constructions

Lecture Annotations

For each asynchronous lecture, please enter at least one annotation in VoiceThread. Your annotation can be a question, comment, hyperlink, short recorded audio comment, or short recorded video comment.

For instructions on how to create annotations in VoiceThread, see the How to Comment page.

Steps Toward Completing a Historical Research Project

Historical Context

- What’s the larger story of a time period?

- How do we organize history anyway, and what is it? Evidence-based narratives and arguments about the past (cause and effect, change and continuity) that we debate.

Historiographic Debate

- What are the questions other historians and interpreters have debated?

- What have they argued?

- How have they agreed or, more crucially, disagreed?

- What evidence did they examine?

- What method did they use to examine it, or how did they interpret their evidence?

- What evidence, perspectives, arguments are missing?

Evidence – Primary Sources

- What sources will you use?

- How do you pay close attention to your source to generate the beginnings of your own interpretation.

Developing a Research Topic, Question, and Workplan

- You’ve explored the context, you’ve taken in the historiographic debate, you’ve zoomed in to investigate one historical primary source yourself (doesn’t have to be one you stick with). Now it’s time to map out a plan for your project.

Some Practical Advice: Notetaking and Bibliographic Records

- How do I track my secondary sources?

- Use Zotero.

- Other possibilities can be Endnote, DevonThink, or a database of your own devising.

- How do I track my own primary source research. There are many ways to do so. I like to:

- Maintain a research journal. I use Evernote and a regular old paper notebook and pen, but you can use any note taking or word processing application, or just a notebook and pen or pencil.

- Keep your digital files organized. If you are downloading digital files, developing a good naming system so you can find things. Use those names in your notes so you can locate what you need. *Backup your files* often to OneDrive (free from Brockport) or an external hard drive or some other cloud-based service you use.

- If you are in an actual archive, post-Covid, a great tool for organizing archival photos of documents is Tropy.

- Play around with your own system. What works for you to track sources both primary and secondary and take notes.

Get Support

- Librarians rule! Go meet with one, discuss your project, ask about how to navigate library resources (interlibrary loan, databases of articles, reviews and review essays, archives digital or analog, and so on)

- History-expert writing tutors rule too! You need people with whom you can talk about your project. Talk to one. Show them your earliest first ideas. Get feedback.

Maintain Good Notes and Bibliographies

- You need to cite your sources accurately in historical research. You also need a plan for tracking your sources, your notes, your ideas. See above step on note taking and bibliography tools.

Research, Write, Outline, Revise, Get Feedback — Research, Write, Reverse Outline, Revise, Get Feedback — Repeat

- Historical research and writing is an iterative process, which means it isn’t a sequence, but an engaged effort at repeating tasks with variation. Not a straight line of steps but more often than not a kind of corkscrew in which you make progress by circling around a project. It’s a kind of craft at which you really have to live with a project and rework it to bring it to clarity and make your evidence-based narrative and argument about the past compelling and convincing.

Give Yourself Time

- To Proofread

- To Check Your Citations

- To Bring Your Project to the Finish Line

Writing Consultation

Writing Tutors are available through the Academic Success Center and are always helpful at any stage of writing.

The history writing tutor specialists are:

- Jacob Tynan: M 12:30-5:30; T 10-3; Th 10-3

- Glenn Dowdle: M 12-1; T 12-2; W 12-4; Th 12-2; F 12-1

You can request them specifically or work with one of the other tutors as needed.

Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer.

Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote.

Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy.

For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website.

Grading Standards

Grading Standards

Remember to honor the Academic Honesty Policy at Brockport, including no plagiarism. Confused about what constitutes plagiarism? Don’t hesitate to ask.

A-level work is outstanding and reflects a student’s:

- regular attendance, timely preparation, and on-time submission of assignments

- thorough understanding of required course material

- insightful, constructive, respectful and regular participation in class discussion

- clear, compelling, and well-written assignments that include

- a credible argument with some originality

- argument supported by relevant, accurate and complete evidence

- integration of argument and evidence in an insightful analysis

- excellent organization: introduction, coherent paragraphs, smooth transitions, conclusion

- sophisticated prose free of spelling and grammatical errors

- correct page formatting when relevant

- excellent formatting of footnotes or other form of required documentation

B-level work is good, but with minor problems in one or more areas

C-level work is acceptable, but with minor problems in several areas or major problems in at least one area

D-level work is poor, with major problems in more than one area

E-level work is unacceptable, failing to meet basic course requirements and/or standards of academic integrity/honesty

As my colleague Jason Mittell likes to say, we use grades to evaluate specific work in a class and to try to improve our abilities with a topic of study. They are never a judgment of you as a person. I value and respect all of you no matter what grade you receive.

Grade Breakdown

Assignment 01-12 = 5 x 12 = 60%

Final Project = 25%

Lecture Annotations = 5%

Participation = 10%

Attendance Policy

Attendance is mandatory. Students are allowed two absences for the semester, no questions asked. These include absences for any reason. Each additional absence may lower your grade at the instructor’s discretion. Please contact the instructor if you have questions. Four unexcused absences are grounds for course failure.

The Importance of Academic Honesty

Academic dishonesty, particularly in the form of plagiarized assignments (question sheets, essays), will result in failed assignments, possible course failure, official reporting, and potential expulsion from Brockport. The Brockport Academic Honesty policy applies to all work in this course. To be certain about its stipulations, rather than risk severe penalties, consult it on the College website. If you have additional questions about the Academic Honesty policy, please consult the instructor.

Disabilities and Accommodations

As the father of a child with neuroatypicality, Professor Kramer recognizes that students may require accommodations to learn effectively. In accord with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Brockport Faculty Senate legislation, students with documented disabilities may be entitled to specific accommodations. SUNY Brockport is committed to fostering an optimal learning environment by applying current principles and practices of equity, diversity, and inclusion. If you are a student with a disability and want to utilize academic accommodations, you must register with Student Accessibility Services (SAS) to obtain an official accommodation letter which must be submitted to faculty for accommodation implementation. If you think you have a disability, you may want to meet with SAS to learn about related resources. You can find out more about Student Accessibility Services or by contacting SAS via sasoffice@brockport.edu, or (585) 395-5409. Students, faculty, staff, and SAS work together to create an inclusive learning environment. As always, feel free to contact the instructor with any questions.

Discrimination and Harassment Policies

Sex and gender discrimination, including sexual harassment, are prohibited in educational programs and activities, including classes. Title IX legislation and College policy require the College to provide sex and gender equity in all areas of campus life. If you or someone you know has experienced sex or gender discrimination, sexual harassment, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, or stalking, we encourage you to seek assistance and to report the incident through these resources. Confidential assistance is available on campus at Hazen Center for Integrated Care and RESTORE. Faculty are NOT confidential under Title IX and will need to share information with the Title IX & College Compliance Officer. For these and other policies governing campus life, please visit the College-Wide Student Policies webpage.

Additional Policies

History Department Student Learning Outcomes

- Articulate a thesis (a response to a historical problem).

- Advance in logical sequence principal arguments in defense of a historical thesis.

- Provide relevant evidence drawn from the evaluation of primary and/or secondary sources that supports the primary arguments in defense of a historical thesis.

- Evaluate the significance of a historical thesis by relating it to a broader field of historical knowledge.

- Express themselves clearly in writing that forwards a historical analysis.

- Use disciplinary standards (Chicago Style) of documentation when referencing historical sources.

- Students will identify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ work.

- Students will write and reflect on the writing conventions of the disciplinary area, with multiple opportunities for feedback and revision or multiple opportunities for feedback.

- Students will demonstrate understanding of the methods social scientists use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of interpretive analysis.

- Students will demonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of history.

- Students will develop proficiency in oral discourse and evaluate an oral presentation according to established criteria.

Emergency Alert System

In case of emergency, the Emergency Alert System at The College at Brockport will be activated. Students are encouraged to maintain updated contact information using the link on the College’s Emergency Information website. Included on the website is detailed information about the College’s emergency operations plan, classroom emergency preparedness, evacuation procedures, emergency numbers, and safety videos. In addition, students are encouraged to familiarize themselves with the Emergency Procedures posted in classrooms, halls, and buildings and all college facilities.

Mandatory Covid-19 Safety Measures to Protect You and Our SUNY Brockport Community

SUNY Brockport’s primary concern during this COVID-19 pandemic focuses on the safety, health, and well-being of students and the college community.

Your compliance with these mandatory safety measures will help reduce the likelihood of COVID cases and keep our campus safe so we can convene in-person classes and student activities. Failure to follow the directive of a college official will result in a referral to the Student Conduct Board and appropriate actions will be taken. Please note, you will be asked to leave the classroom if your behavior endangers yourself or others by not following safety directives set by the college and a referral to the Student Conduct Board will be made. As per the Code of Student Conduct, Failure to Comply with the directive of a college official could result in disciplinary action, including but not limited to removal from the residence halls and/or suspension.

Student cleaning requirements: Wipe your work surface (desk or table) and seat prior to use with the disinfectant wipe effective against COVID19 provided in the classroom. Deposit the used wipe in a classroom garbage receptacle. If shared items are used in the classroom, disinfect them before and after use.

Seating & Social Distancing:

- Do not occupy seats that are marked “Do not sit.”

- Maintain social distance (stay 6’ apart) from others in the classroom to the extent possible.

Face covering: Wear an appropriate face covering that covers your nose and mouth at all times. You may lift your mask briefly to take a drink. Eating is not permitted inside the classroom. Please see the attached link for specific information regarding Social Distancing and Face Covering Policy.

Healthy Practices:

- Do not report to class if you are feeling ill. Leave class quietly and immediately if you are feeling unwell and notify your instructor as soon as you able to.

- Follow respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette. Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth, and wash your hands after touching your face. Cover coughs and sneezes. Wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds especially after you have been in a public place, or after blowing your nose, coughing, sneezing, or touching your face. If soap and water are not readily available, use a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. While hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol is widely available throughout the campus, it is less effective than washing with soap and water. Washing your hands often is considered the best practice.

Any student who feels ill or has any medical needs should contact the Student Health Center at (585) 395-2414 or your personal physician to discuss your symptoms. If you think you need to see a medical professional, contact the Student Health Center to make an appointment first as there are no walk in hours at this time. Students who experience significant cough, worsening of chronic asthma symptoms, a fever that lasts more than two to three days, dizziness, and/or dehydration should be evaluated. If symptoms are severe and urgent assistance is needed, contact the Student Health Center and/or University Police on campus (585) 395-2222 or 911 if off campus.

Emergency evacuation considerations:

In the event of an evacuation alarm, everyone should immediately find the nearest exit, leave the building, and proceed to an assembly area with a face covering on and maintain social distance from others to the extent possible. While it is important to maintain social distance, you should not delay exiting the building in order to do so in the event of any emergency. In areas where separate entrances/exits have been established, it is important to note that these do not apply in the event of an emergency. Individuals should use the nearest exit. When re-entering the building, maintain social distance from others. Upon re-entering the building, avoid congregating in the entranceway or lobby. Take the stairs instead of the elevator whenever possible.

Assignment 01 Course Contract and Student Info Card

Please create an MS Word document and respond to the following questions so I can begin to get to know each of you a little better. This document also serves as a Course Contract acknowledging that you have thoroughly read the Start Here module of the website.

Paste the following template and then respond.

- Name:

- Year at Brockport:

- Circle the pronoun you prefer— he/him, she/her, they/them — or if another referral form you wish me to use, let me know here:

- Best contact info in an emergency (phone, email, text):

- Review the Start Here module on Canvas. What did you notice most about it? What questions do you have about it?

- What do you most want to get out of the content of this course (other than an A)?

- When is the furthest back you can trace your own family’s history? To where?

- What other things should I know about you as your professor in this class (interests, concerns, special needs, worries, hopes)?

- Any other questions right now for me (you can always ask me questions as they arise during the semester)?

- I have read the Start Here module of the course website and agree to honor the policies and rules for the course.

- Sign here (you may draw your signature or type your name):

- Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Welcome to HST 390 Fall 2020 Edition! I am excited to work with you this semester. Prof. Kramer

Weeks 01-02 Getting to Know a Time Period & Topic

Week 01

This Week

This week, we begin the process of research. We’ll be focusing on the primary sources from the digital repository of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival collection, developing your research and writing (and thinking!) skills when it comes to history, and exploring how to analyze not only classic textual documents, but also other kinds of historical evidence such as images, spaces, things, sounds, and more. How do we reconstruct and develop interpretations of the past using all we can to do so? The Berkeley archive is our “home base,” but we will also journey out to other materials, topics, methods, and tactics of studying the past.

Asynchronous—Welcome and Getting Started

Week 01 Required Materials

- Barry Olivier, “Folk music at Berkeley 1956 to 1970,” Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

- Barry Olivier, “Berkeley Folk Music Festival history and collection,” Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

- American Roots Music Episodes 01

- Listening Mix: Introduction to Folk

- Take a look at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Topics page just to start to get a sense of what you are working toward for your final project.

- Take a look at the Steps Toward Completing a Historical Research Project page.

Synchronous Discussion—Welcome and Getting Started

Week 02

This Week

This week we are focusing on the broad historical context of the postwar decades after World War II. We will also consider the broader terms we use to study history. What do we even mean by “broad historical context,” for example.

You might think about a few questions for this week.

The first are particular to how we characterize this era:

- What are the overarching themes of this period in US history?

- What are the important events of this era?

- Who are the important figures of this era?

- Who had power during this time period? Why?

- Who lacked power and why?

- What were the important institutions in American life during this time period?

- Who had “agency,” or the ability to cause things to change or stay the same, during this era? Why (or why not)?

- What makes sense about this era and what does not to you as you learn about it?

Then, some larger historical and theoretical questions?

- How do we choose to organize periods of history? Some call this “periodicity.” Would the story be different if we started with a different beginning and ended with a different conclusion?

- What is historical “context” exactly? What is “context”? (for a fascinating essay about this concept, see Daniel Wickberg’s “The Idea of Historical Context and the Intellectual Historian,” in American Labyrinth: Essays in U.S. Intellectual History, eds. Raymond Haberski and Andrew Hartman (Cornell University Press, 2018)?

- What are “primary sources” compared to “secondary sources”?

- What are “archival sources” exactly?

- What is a historical argument or interpretation? How is it different from other kinds of evidence-based analyses?

- What makes a historical interpretation convincing or compelling? What doesn’t?

Week 02 Required Materials

- Foner, Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 23: The United States and the Cold War, 1945-1953, 705-733

- Foner, Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 24: Chapter 24: An Affluent Society, 1953-1960, 734-765

- Foner, Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 25: The Sixties, 1960-1968, 766-802

- Listening Mix: Introduction to Folk

- Take a look at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Topics page just to start to get a sense of what you are working toward for your final project.You read Director Barry Olivier’s reflections on the Berkeley Folk Music Festival and the Archival Collection he sold to Northwestern University in 1973. Now just to start exploring, browse around a bit in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository and A/V repository just to see what’s there. Try typing in search terms (names, instruments, places). Additionally, you can navigate the archive using the draft of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository Finding Aid. Start to get a feel for this archive we will be working with during the semester.

Asynchronous—Thinking About Historical Context: The US After WWII

Synchronous Discussion—Historical Context

Assignment 02 Historical Timeline and Context

Your task is to develop an overarching sense of the big themes and events of the post-World War II period in the US and the world. Use an MS Word document to complete your assignment. Your responses can be numbered as below. Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Timeline

- Using pen/pencil and a piece of paper or MS Word or another software application, create a timeline of the years 1945 to 1970.

- Place what you take to be the most important 5-10 events on the timelines by date.

- Take a picture of your timeline (a smartphone camera will do). Embed the image in your MS Word document. Or if you created the timeline using software, cut and paste it into your MS Word doc.

- If you wish to experiment with a digital tool, try experimenting with Timeline.js, a free digital timeline tool that uses a Google Sheet of data to create a multimedia timeline. Include the URL (web address) link to your Timeline in your assignment, or link to your timeline from a page in our class WordPress website. This is not required, just if you are curious to explore a digital tool.

Historical Context

- How would you characterize the decades after WWII in the United States and the world, from 1945 to 1970? Write a short one-two paragraph reflection in which you select at least two short quotations from Eric Foner’s textbook chapters and explain what they mean and why they matter to your larger characterization of the era.

- If you were to characterize progress during this era, how would you characterize it? Write a short paragraph in which you interpret the era of 1945 to 1970 as one of American progress. Use three particular examples (events, stories, developments) to support your argument.

- If you were to characterize decline during this era, how would you characterize it? Write a short paragraph in which you interpret the era of 1945 to 1970 as one of American decline. Use three particular examples (events, stories, developments) to support your argument.

- Now try to imagine characterizing the postwar decades neither as progress, nor as decline. How would you characterize it? Use three particular examples (events, stories, developments) to support your argument.

Weeks 03-04 Framing a Historiographic Debate

Week 03

This Week

This is a week to read and watch and absorb information.

I am asking you to do a fair bit of reading and viewing, so prepare yourself to take some time to read and watch. Your goal is to begin to absorb the historiography, which is to say the debates among historians of the folk revival about its history. We’ll be reading a few different interpretations. You might think about what their arguments are, what sources they use, and what methods they employ to develop their interpretations of the revival.

- What does each writer most care about from your perspective?

- When was each of these interpretive essays written?

- Hey, wait a minute, you might say, that first one by Ellen Stekert is almost a primary source, written during the time period. Exactly! What is the line between a primary source and a secondary one? Notice how even in the moment, primary sources already start to create interpretations of their historical moment. These often continue to shape the subsequent historiography (does Stekert’s? If so, how?). They also serve as a reminder that the line between primary and secondary source is not precise, but ambiguous and porous.

- You could even flip the switch here: when was each later secondary source written and does that historical moment/context shape its interpretation of the 1960s folk revival? Remember, as we write about history, we are also in it!

We’re also going to continue watching the documentary film American Roots Music. This documentary was released just at the end of the 1990s. How does it characterize the history of the folk revival? Pay particular attention to the opening sequence, which frames the interpretation of the rest of the episodes. Try to take notes as you watch: what’s something that catches your ear or eye and why?

Week 03 Required Materials

- Bruce Jackson, “The Folksong Revival,” in Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined, ed. Neil V. Rosenberg (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 73-83

- Ellen J. Stekert, “Cents and Nonsense in the Urban Folksong Movement: 1930-1966,” in Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined, ed. Neil V. Rosenberg (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 84-106

- Elijah Wald, “Introduction” and “The House That Pete Built,” in Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties (New York: Dey Street Books, 2015, 1-32

- Robert Cantwell, “When We Were Good: Class and Culture in the Folk Revival,” in Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined, ed. Neil V. Rosenberg (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 35-59

- Grace Elizabeth Hale, “Black as Folk: The Folk Music Revival, the Civil Rights Movement, and Bob Dylan,” in A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America, 84-131

- American Roots Music Episode 02

- Listening Mix: Introduction to Folk

Asynchronous—Framing Historiography: Debating the Folk Revival

Synchronous Discussion—Framing Historiography: Debating the Folk Revival

Week 04

This Week

This week we continue to explore the concept and practice of historiography as we also begin look to some primary sources from the folk revival itself as already engaged in secondary source thinking about the historical moment in which they were written. How can one draw critically upon the frameworks for a historical time period embedded in primary sources themselves?

Week 04 Required Materials

- Alan Lomax, “The ‘Folkniks’—and the Songs They Sing,” Sing Out! 9 (1959): 30-31, reprinted in Alan Lomax, Selected Writings, 1934-1997

- John Cohen, “In Defense of City Folksingers,” Sing Out! 9 (1959), 33-34

- Pete Seeger, “Why Folk Music?” International Musician (1965), reprinted in The American Folk Scene, 44-49

- Sam Hinton, “The Singer of Folk Songs and His Conscience,” Western Folklore 14, 3 (1955): 170-173; reprinted in Sing Out! 7, 1 (Spring 1957), 24-26

- Festival, dir. Murray Lerner (1967)

- American Roots Music Episode 03

- American Roots Music Episode 04

Synchronous Discussion—Framing Historiography: Debating the Folk Revival Part Two

Assignment 03 Framing a Historiographic Debate

Your task is to describe and develop an argument about two of our readings concerning folk revival historiography. Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Your essay should be about 1000-1500 words approximately, enough room to develop an evidence-based interpretation and stretch out a bit, but also a length that requires you to draft, edit, revise, and tighten your writing effectively. Be sure to draft, edit, consult, and revise. Writing Tutors are available through the Academic Success Center and are always helpful at any stage of writing. Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer. Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Develop a cogent, compelling, evidence-based interpretation of the two essays. How do they compare? What is similar in their arguments, use of evidence, and perspectives on the folk revival’s history? What diverges? Make sure to develop your own argument based on close reading of the essays, particularly through surgical quotation tactics of evidence (keywords, key phrases, but avoid long quotations) from the essays. Be sure your essay has a good opening, states its argument, has topic sentences, transition sentences, and a strong conclusion. Try to write with style: avoid clunky phrasing, passive voice, and phrases such as “throughout history.” Write a draft, meet with a writing advisor, and revise before the assignment is due. For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website.

Weeks 05-07 Developing a Research Agenda

Week 05

This Week

This week we shift from secondary to primary source artifacts, focusing not only on how to analyze text and language, but also non-textual primary sources such as sound, music, images, film, material culture, and data. You will also explore and start to narrow down to a topic for your final research project. See the list of Berkeley Folk Music Festival Topics for more details.

Asynchronous—Writing About Textual & Non-Textual Sources

Week 05 Required Materials

- Jules David Prown, “Methodology,” in “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” Winterthur Portfolio 17, 1 (April 1982): 7-10

- Michael J. Kramer, “The Multitrack Model: Cultural History and the Interdisciplinary Study of Popular Music,” in Music and History: Bridging the Disciplines, edited by Jeffrey H. Jackson and Stanley C. Pelkey (University Press of Mississippi, 2005), 220-255

- Larry Starr and Christopher Waterman, American Popular Music: From Minstrelsy to MP3, 4th edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), Ch. 1, 5-44

- Berkeley Folk Music Festival Topics

Berkeley Folk Music Festival Topics

Biographical focus: I suggest focusing your final project on a performer, using her, his, or their biographies as a focus for a larger argument. Look at Barry Olivier’s Berkeley Folk Music Festival overview for a partial list of performer names. There are plenty others who appear in the archive as well. Confer with Professor Kramer about your interests to locate a performer or performers who can become the focus of your final project.

There also might be other topics and themes that interest you based on sources found in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository. These might connect to a biographical focus or perhaps take you in a slightly different direction. For example:

- A study of one song or set of songs, investigating and analyzing its history, circulation, music and text, and significance.

- A study of a particular genre or boundaries between or among genres.

- A study of an event, or aspect of an event from sources contained within the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository.

- A study of politics or some issue of cultural politics related to artifacts in the archive.

- A study of change (and/or continuity) over time of a performer, event, or theme.

- The notion of a folk “revival”—revival of what, exactly? On whose terms? To what end?

- The concepts of authenticity, sincerity, irony, and other modalities or sensibilities and values of the folk revival.

- Concepts of the audience and of participation in the folk revival.

- Concepts of tradition and heritage in the folk revival.

- Issues of race, gender, ethnicity, region, age, economics (capitalism), politics (socialism) as registered in specific source material and secondary debates.

- Folk music as an educational tool (or not).

- An exploration of the meaning of one artifact: a photograph, a document, an album cover, an instrument, a famous article, or some other source material and what it reveals about a larger theme.

- What is missing from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival? How might your project explain that absence and fill it in with fresh archival and historiographic research in your final project?

Synchronous Discussion—Writing About Textual & Non-Textual Sources

Assignment 04 Writing About A Source

A research agenda is a working document to help you map out your research project plan and progress to completing it. It should include responses to the following questions. Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Be sure to draft, edit, consult, and revise. Writing Tutors are available through the Academic Success Center and are always helpful at any stage of writing. Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy. For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website. Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Research Agenda

- Name

- Date

- Research topic (selected from Berkeley Folk Music Festival Topics)

- Research question—What overarching historical question do you wish to ask about your topic?

- Primary sources—A list of specific primary sources will you use to investigate this question from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository and Audio/Video Repository. You can go to the repository directly or use the draft of the digital finding aid to explore it by box and folder (as it existed in the analog archive): Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Finding Aid. Try to include as much bibliographic information as possible, but don’t worry about proper citation for now, just get your list assembled.

- Additional potential primary sources—A list of digital archives, artifacts, articles, recordings, films, etc. Try to include as much bibliographic information as possible, but don’t worry about proper citation for now, just get your list assembled.

- Secondary sources—With what secondary sources do you plan to place your research in dialogue? Try to include as much bibliographic information as possible, but don’t worry about proper citation for now, just get your list assembled.

- Why is this topic interesting? Why does it matter? What are its stakes for understanding the historical past? What have other historians and commentators had to say about the topic? How would you engage in a dialogue with their interpretations?

- Imagine a tentative working title for your project.

Work Plan

- Develop a draft of a weekly schedule for completing your research, drafting, and completion of your project by the due date.

Create a Zotero Account (Or Similar, such as Endnote)

- Zotero is a useful free online tool for maintaining a digital bibliography. It was created by historians at the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. Try it out. You can install a plug in for your browser that lets you export bibliographic data directly from WorldCat, Amazon, and other databases. Download here.

Start a Research Journal (or Journals)

- I use a notebook and pen AND a digital journal (I like Evernote, but you can use Microsoft’s OneNote, Apple Notes, or any other journal/notetaking application of your liking. You can even just use a Microsoft Word document or Text Editor. Use it to jot down sources, write ideas, sketch out pictures of your research, record your daily process, try out titles, whatever you find useful.

Week 06

This Week

Welcome to Week 06. Time to start shifting more intensely toward conceptualizing and starting in on your final project this week.

Week 06 Required Materials

Some more secondary readings depending on your developing research interests.

Select one or more of the following to read or watch.

Readings

- Neil V. Rosenberg, “Introduction,” Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined, ed. Neil V. Rosenberg (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 1-25

- Benjamin Filene, “Introduction,” Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 1-9

- Ronald Cohen, “The 1960s” and “Newport,” in A History of Folk Music Festivals in the United States: Feasts of Musical Celebration (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009), 57-113

- Sheldon Posen, “On Folk Festivals and Kitchens: Questions of Authenticity in the Folksong Revival,” Transforming Tradition, 127-136

- David Blake, “‘Everybody Makes Up Folksongs’: Pete Seeger’s 1950s College Concerts and the Democratic Potential of Folk Music,” Journal of the Society for American Music12, no. 4 (November 2018), 383–424

- Warren Bareiss, “Middlebrow Knowingness in 1950s San Francisco: The Kingston Trio, Beat Counterculture, and the Production of “Authenticity,’” Popular Music and Society, 33, 1 (February 2010), 9–33

- Ray Allen, “In Pursuit of Authenticity: The New Lost City Ramblers and the Postwar Folk Music Revival,” Journal of the Society for American Music 4, 3 (August 2010), 277–305

- Amanda Petrusich, “The Discovery of Roscoe Holcomb and the ‘High Lonesome’ Sound,” New Yorker, 17 December 2015

- David A. DeTurk and A. Poulin, Jr., “Preface” and “Introduction: Speculations on the Dimensions of a Renaissance,” in The American Folk Scene: Dimensions of the Folksong Revival, eds. David A. DeTurk and A. Poulin, Jr. (New York: Dell, 1967), 13-34

- B.A. Botkin, “The Folksong Revival: Cult or Culture?,” in The American Folk Scene, 95-100

- Kerran L. Sanger, “When the Spirit Says Sing!”: The Role of Freedom Songs in the Civil Rights Movement (New York: Garland, 1995), Introduction, Section 1, 1-63

- Shana Redmond, “Soul Intact: CORE, Conversions, and Covers of ‘To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora (New York: New York University Press, 2014), Chapter 5, 179-220

- Jeff Todd Titon, “Reconstructing the Blues: Reflections on the 1960s Blues Revival,” in Transforming Tradition, 220-240

- Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., “Blues and the Ethnographic Truth,” Journal of Popular Music Studies13, 1 (2001), 41–58

- Josh Garrett-Davis, “The South Stole Americana,” LA Review of Books, 5 January 2016

- David W. Samuels, “Singing Indian Country,” in Music of the First Nations: Tradition and Innovation in Native North America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 141-160

- John Koegel, “Crossing Borders: Mexicana, Tejano, and Chicana Musicians in the United States and Mexico,” in From Tejano to Tango: Latin American Popular Music, ed. Walter Aaron Clark (New York: Routledge, 2002), 97-125

- Conduct your own research: what readings can you discover about your topic? Biographies, recordings, academic articles, journalistic articles, additional archival sources, films, oral histories? Use the Drake Library website and meet with a librarian to discuss and research!

Films

- Let Freedom Sing: How Music Inspired the Civil Rights Movement, dir. Jon Goodman (2009)

- Soundtrack for a Revolution, dir. Bill Guttentag (2010)

- Pete Seeger: The Power of Song, dir. Jim Brown (2007)

- Joan Baez: How Sweet the Sound, dir. Mary Wharton (2009)

- No Direction Home: Bob Dylan, dir. Martin Scorsese, Episodes 01 and 02 (2005)

- Always Been a Rambler: Celebrating 50 Years of the New Lost City Ramblers, dir. Yasha Aginsky (2009)

- Phil Ochs: There But For a Fortune, dir. Kenneth Bowser (2011)

- American Epic, dir. Bernard MacMahon, Episodes 01, 02, 03 (2015)

- Why Old Time?, dir. Chris Valluzzo and Sean Kotz (2010)

- In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey, dir. James Cullingham (2012)

- Explore the films on Folkstreams

- There are many more documentary films to access and explore depending on your developing research topic. Consult with Professor Kramer and meet with a librarian for a research appointment.

Synchronous Discussion—Week 06—Open

Assignment 05 Research Topic Pitch

Your task is to develop two different “pitches” for a topic you want to focus on for your research project based on the list of potential topics or a topic of your own devising linked to Berkeley Folk Music Festival sources. You may imagine ways of linking these primary sources to other historical themes, to contemporary music of interest to you, or to some other topic that you wish to research. Feel free to browse through the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository and its audio-video sources too.

Each of your two different pitches should include numbered responses as below. Then rework your responses into a paragraph to explain:

- What the topic is.

- Why does the topic interest you?

- What theme you might imagine linking the topic to?

- Potential primary and secondary sources you might explore beyond the Berkeley Folk Music Festival (you can be very tentative about this at this point).

Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Be sure to draft, edit, consult, and revise. Writing Tutors are available through the Academic Success Center and are always helpful at any stage of writing. Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy. For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website. Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Week 07

This Week

Week 07 is a key week to begin to deepen your research on your final project. Don’t delay, get going! You’ll thank yourself at the end of the semester for the work you do now.

Synchronous Discussion—Week 07—Open

Assignment 06 Librarian Research Meeting Report

Now that you have a research topic and the beginnings of some hypotheses and directions for further research, this week you should meet with a librarian either in person at Drake Library or online. **Be sure to schedule an appointment.**

Librarians and archivists are invaluable consultants on research resources. You can discuss how to search for additional secondary sources (books, essays, recordings (yes you can obtain these through the library, you don’t need to buy them!), liner notes, film documentaries and other video resources, websites, and more). What stuff is out there for you to use, learn from, and incorporate into your research project?

You should file a report about your meeting. It should feature numbered responses as below:

- Current topic of research project

- Time of meeting with librarian

- List of potential secondary sources

- List of potential additional primary sources beyond the Berkeley archive

- One paragraph reflection on what you learned from the meeting about your research project’s potential directions, connections, possibilities.

- One paragraph reflection: what are you concerned about with your research project? What problems do you currently see with the project?

Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Don’t hesitate to consult with a writing tutor! Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy. For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website. Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Week 08-09 Researching & Drafting

Week 08

This Week

This week we continue to take steps toward developing a successful final project.

Asynchronous—Developing a Research Agenda & Work Plan

Synchronous Discussion—Week 08—Open

Week 09

This Week

By the end of this week you will have developed a Research Agenda & Work Plan.

Synchronous Discussion—Week 09—Open

Assignment 07 Research Agenda & Work Plan

A research agenda is a working document to help you map out your research project plan and progress to completing it. It should include responses to the following questions. Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Be sure to draft, edit, consult, and revise. Writing Tutors are available through the Academic Success Center and are always helpful at any stage of writing. Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy. For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website. Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Research Agenda

- Name

- Date

- Research topic (selected from Berkeley Folk Music Festival Topics)

- Research question—What overarching historical question do you wish to ask about your topic?

- Primary sources—A list of specific primary sources will you use to investigate this question from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository and Audio/Video Repository. Try to include as much bibliographic information as possible, but don’t worry about proper citation for now, just get your list assembled.

- Additional potential primary sources—A list of digital archives, artifacts, articles, recordings, films, etc. Try to include as much bibliographic information as possible, but don’t worry about proper citation for now, just get your list assembled.

- Secondary sources—With what secondary sources do you plan to place your research in dialogue? Try to include as much bibliographic information as possible, but don’t worry about proper citation for now, just get your list assembled.

- Why is this topic interesting? Why does it matter? What are its stakes for understanding the historical past?

- Imagine a tentative working title for your project.

Work Plan

- Develop a draft of a weekly schedule for completing your research, drafting, and completion of your project by the due date.

Week 10-12 Drafting (& Researching More & Reframing Historigraphical Debate)

Week 10

This Week

This week we will continue the hard work of researching, drafting, and revising. Note that you don’t do these in sequence necessarily but in a circular dynamic with one another. Keep going, asking yourself what is puzzling you, how to streamline your work, and giving yourself some time as well to explore some darker, uncertain pathways of research and writing. If you aren’t yet, start a research journal of your daily thinking, musings, curiosities, worries, and triumphs with your research.

Asynchronous—Document Analysis, Outlining & Very Rough Drafting

Synchronous Discussion—Week 10—Open

Assignment 08 Document Analysis 01

Once again, your task is to practice close analysis, or what is often called “close reading” of a source. Select one artifact from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository that you are working with for your project. Develop a one-paragraph close reading of the artifact. You can write about a text, an image, audio, or even video.

- Think about description first: what do you see? What do you hear? Focus on the artifact’s details. Write these out.

- What do the details make you think about in terms of the context for the artifact? When is it from? Where is it from? What did it make you think about?

- What does it mean? Try to write a one sentence interpretation of the artifact. What is its significance and why? Tips:

- add the word “because” to the end of your sentence and see if you can explain why an artifact matters.

- think about developing a comparison or contrast: what is similar or different about the details of this artifact compared to some other one?

- consider larger theoretical concepts: what does this artifact tell us about race, gender, class, region, identity, power, representation, agency, structure, institutions, causal forces, injustice, freedom, or resistance, just to consider a few themes? How does it express some aspect of those themes in relation to its historical context and moment?

Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Your assignment should be one paragraph long. Be sure to draft, edit, consult, and revise. Writing Tutors are available through the Academic Success Center and are always helpful at any stage of writing. Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy. For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website. Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Week 11

This Week

This week we keep on keeping on with research, primary source analysis, secondary source reading and processing, research journal entries, and drafting.

Synchronous Discussion—Week 11—Open

Assignment 09 Document Analysis 02

Once again, your task is to practice close analysis, or what is often called “close reading” of a source. Select another artifact from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository that you are working with for your project. Develop a one-paragraph close reading of the artifact. You can write about a text, an image, audio, or even video.

- Think about description first: what do you see? What do you hear? Focus on the artifact’s details. Write these out.

- What do the details make you think about in terms of the context for the artifact? When is it from? Where is it from? What did it make you think about?

- What does it mean? Try to write a one sentence interpretation of the artifact. What is its significance and why? Tips:

- add the word “because” to the end of your sentence and see if you can explain why an artifact matters.

- think about developing a comparison or contrast: what is similar or different about the details of this artifact compared to some other one?

- consider larger theoretical concepts: what does this artifact tell us about race, gender, class, region, identity, power, representation, agency, structure, institutions, causal forces, injustice, freedom, or resistance, just to consider a few themes? How does it express some aspect of those themes in relation to its historical context and moment?

Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Your assignment should be one paragraph long. Be sure to draft, edit, consult, and revise. Writing Tutors are available through the Academic Success Center and are always helpful at any stage of writing. Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy. For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website. Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Week 12

This Week

This is a big week! You have been working along and it’s time to make that final push to develop a full outline and very rough draft of your final project.

Synchronous Discussion—Week 12—Open

Assignment 10 Outline and Very Rough Draft

Time to get that first rough draft on paper. But guess what? You have your Research Topic Pitch, Research Agenda & Work Plan, and your two Document Analyses to work with as you develop an outline and very rough draft for your final project. Use them! For this assignment you should create an outline. Keep the outline intact and write your draft between its lettered and numbered points.

Your outline should consist of:

- Potential title of your project.

- Introduction – a representative vignette that hooks a reader into your topic

- Your overarching argument stated clearly

- Body paragraphs each with:

- A topic sentence

- Specific evidence examples

- Conclusion concept – how might you end your essay strongly, leaving the reader with a last idea that restates and then expands upon your overarching argument

Then, write your Very Rough Draft within the lettered and numbered outline. It can be very rough. Just write, don’t worry about precision at this point. That will come with subsequent revision.

Your assignment should look like this:

TITLE

Name

I. Introduction

II. Thesis/Argument

II. Body paragraph one topic sentence

A. Evidence

B. Evidence

(you should have at least one piece of evidence, but can have more if supporting your argument effectively requires it)

II. Body paragraph two topic sentence

A. Evidence

B. Evidence

(you should have at least one piece of evidence, but can have more if supporting your argument effectively requires it)

As many paragraphs as you think your essay requires.

II. Body paragraph two topic sentence

A. Evidence

B. Evidence

(you should have at least one piece of evidence, but can have more if supporting your argument effectively requires it)

As many body paragraphs as needed, probably anywhere from 8-15.

XV. (or whatever number you reach) Conclusion topic sentence or at least a concept for the conclusion

Consider if your essay needs to be divided up into parts or sections after you outline the paragraphs.

Also, **strongly recommended**: make more than one outline of different ideas for structuring your essay. You won’t get the structure right the first time, so save and iterate and try different versions. If you save the iterations you can return to earlier ideas if they clarify as the best structure for your essay.

Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins. Be sure to draft, edit, consult, and revise. Writing Tutors are available through the Academic Success Center and are always helpful at any stage of writing. Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Remember not to plagiarize according to Brockport’s Academic Honesty policy. For additional information see the What Makes for Good Work? page of the course website. Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Week 13 Thanksgiving Break

Week 14 Revising (& More Researching & Reframing Historiographic Debate)

Week 14

This Week

This week we return from the Thanksgiving break for the final push toward completing HST 390’s final project.

Asynchronous—The Draft Is Just the Start: Revision

Synchronous Discussion—Week 14—Draft Workshop

Assignment 11 Revision Exercises

You’ve got a draft. This is no small thing. Give yourself some kudos!

This week your task is the all important work of revision and refinement. Pick two of the following exercises to do, depending on instructor feedback on your draft and your own sense of what might be most helpful. Also continue to revise and refine independently. Remember that you can make use of the Writing Tutors, available through the Academic Success Center. Don’t hesitate to consult with someone! Be sure to show them the assignment so they grasp clearly what I am asking you to do as a writer.

Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins for these assignments. Do the best you can to write citations in Chicago style of any materials you reference or quote (we’ll be reviewing citation later in the semester so good to practice here). Questions? Don’t hesitate to contact Professor Kramer. Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

1. Structural issues? Try a Reverse Outline

- Now that you have written a very rough draft, try to redo the outline of the current structure of the essay Save this outline.

- Now try a different outline or structure. See if a different order improves or clarifies the flow of your argument and presentation of your evidence.

- Repeat as needed.

2. Still struggling with articulating your argument? Try 13 Ways of Looking at a Thesis.

- Write out your current thesis.

- Now write it again, changing the language.

- Now try it again. Write it 13 times.

- Now try some variations.

- Write out your thesis without worrying if you are getting it right.

- Try rewriting it as “Whereas X argues, my evidence suggests….” to bring your thesis into more direct historiographic debate with existing interpretations.

- Try rewriting your thesis using method as the key aspect of it. For instance, “Whereas X uses a method of focusing on textual evidence to argue x, my focus on visual evidence suggests a different discover: y.”

- Try writing your thesis about only one primary source artifact you are examining.

- Try writing your thesis as a comparison of one primary source artifact you are examining with another one you are examining.

- Try writing your thesis as a set of keywords and search terms one should use to find it through an online search.

- Try writing your thesis as a debate between two scholars who you have read on the topic or theme you are exploring.

- Try rewriting your thesis as a slogan for an advertisement.

- Try drawing your thesis as a flowchart, Venn diagram, or sketch.

- Try to write the opposite of your thesis. If you were disagreeing with yourself, what would your thesis be.

- Now go back and write out your thesis again and see if it has changed, come alive in a new way, or made you think about revisiting your evidence or secondary sources (what other scholars have argued).

- Take a break and come back to the project later. See what you have.

- For more on this exercise see Michael J. Kramer, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Thesis,” Issues in Digital History, 22 April 2019.

3. Having trouble locating your topic in history? Try a Historical Context exercise.

- Revisit our early work in the course. What is the historical context in which you are positioning your project? Write a paragraph in which you explain how the topic of your project fits with the historical context and why.

4. Having trouble figuring out the significance of your material? Try a Critical Terms As Tools exercise.

- Critical terms serve as tools to help you construct your historical argument and investigate your historical evidence. Select a term and explain in one or two paragraphs why it is the key one to use with your research project topic.

- Race

- Gender

- Class

- Region

- Identity

- Representation

- Power

- Appropriation

- Communication

- Intercultural exchange

- Heritage, Tradition

- Politics vs. Culture

- Economics

- Community

- Private

- Public

- Institution

- Agency

- Structure

- Institutons

- Injustice

- Freedom

- Constraint

- History itself

5. Having trouble writing clear and stylish prose? Try a Sound Revision exercise.

- Read a difficult section of your paper out loud. Record it using your smartphone or a recording device.

- Listen back to it.

- Note what does not flow or quite make sense to you.

- Play it for someone else. Get their feedback.

- Transcribe your prose again from the recording.

- Let yourself change and alter your prose as you transcribe.

- Upload your recording and revision.

- Add a paragraph reflection on what you noticed doing Sound Revision.

Week 15 Reflecting (& More Revising)

Week 15

This Week

Your main task this week is to work on revising your final project. Consider any more primary source research you need to do—or just as often, primary sources you wish to revisit to sharpen your analyses. Develop another outline as needed. Discuss your work with a writing tutor at the Academic Success Center. Recheck or explore any final secondary sources you think might help you clarify the historiographic intervention of your primary source research. Finally, we’ll check in on citation practices using Chicago Manual of Style.

Assignment 12 Citation Tutorial & Practice

Time to sharpen up your citation practice using Chicago Manual of Style, which is the common citation style for history.

Watch the following tutorials. Save any questions for our synchronous discussion.

- Video: Why Citations Matter

- Tutorial: Why Citations Matter

- Video: Chicago Style 17th ed. Journals

- Video: Chicago Style, 17th ed. Books and eBooks

- Video: Chicago Style, 17th ed. Websites and Social Media

- Look up how to cite recordings in Chicago Manual of Style.

- Look up how to cite films in Chicago Manual of Style.

- Practice a few citations in an MS Word doc.

- Submit any questions you currently have about citations in your final project.

Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Synchronous Discussion—Week 15—Draft Workshop

Final Project

Your final project in the course should be a 10-20 page essay based that puts forward an evidence-based argument about a topic from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project in cogent, compelling prose. It should effectively explain a historiographic debate into which your primary historical research makes an intervention, using secondary sources with expertise and precision. It should be clearly structured and gracefully written, with effective and lucid analysis of specific primary source evidence from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Repository and/or A/V Repository as well as at least one other primary source archive.

Use 12-point font, double-spaced, with regular margins with correct citations using Chicago Manual of Style. See the What Makes for Good Work? for more details on effective historical writing. Don’t hesitate to consult with a writing tutor as needed, at any stage of writing!

Upload to Canvas as an MS Word document.

Provide a link to your WordPress post if you have generated any ancillary digital materials such as embedded primary source images, timelines, storymaps, audio, video, or other material.