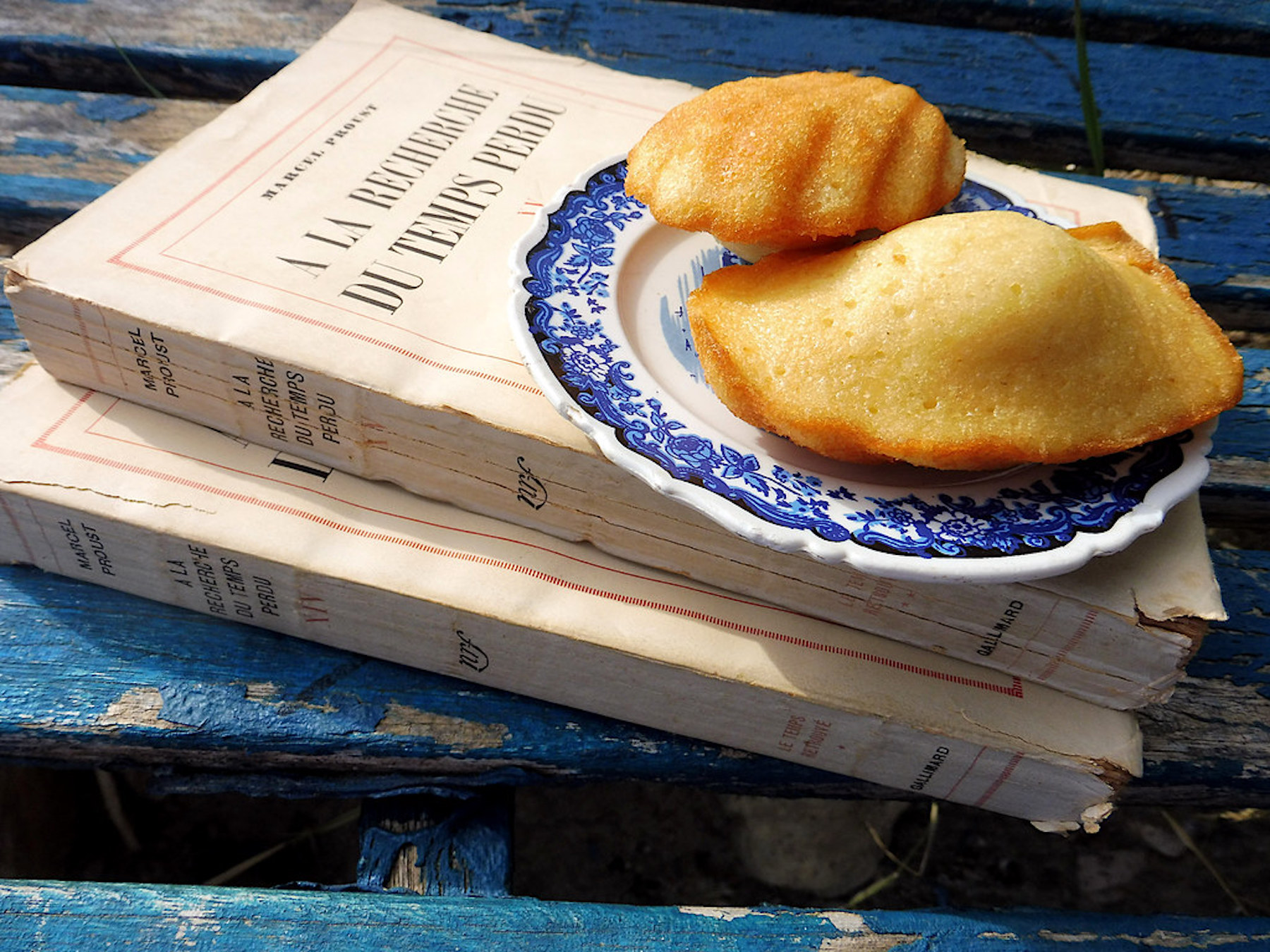

chew on this: proust’s madeleine in reverse.

Infamously, when Marcel Proust tasted a madeleine dipped in lemon-blossom tea, it caused him to experience intense memories of his youth. The Proustian madeleine is now famous as a symbol of how taste and smell can spark the return of repressed or forgotten experiences. But what about when someone loses their sense of taste and smell? What then?

One year ago, as the delta wave of Covid-19 shifted into omicron, I finally caught the virus. Fortunately, my symptoms were fairly mild thanks to vaccination, however I did lose my sense of taste and smell for a few days. This was at once terrifying and fascinating, a kind of psychedelic trip of defamiliarization, a sort of unintended systematic derangement of the senses à la Proust’s almost-contemporary (but quite a different character), Arthur Rimbaud.

Losing one’s sense of taste and smell was a bit like eating a minimalist painting. You know there is a flavor and odor to the food from memory, just as you know that a totally white canvas inside a frame is intended to be a painting, but that’s all you have. The abstract idea remained while the material reality disappeared. The sensory reality was nothing, the imaginary projection became all. Here was Proust’s madeleine, but in reverse! In place of a taste and smell sparking a memory, now all I possessed was the memory of taste and smell.

As Covid-19 itself partially dissipates yet still lingers, we find ourselves in a strange historical moment that dangles between the misty past and the still-circulating present. Might the experience of what we might call Covid-19’s anti-madeleine serve as a kind of metaphor for the larger cultural experience of the era? A time of emptiness, of trauma, of shutdown, of loss, the Covid-19 pandemic currently exists as a kind of void, a blank slate, a memory gap, a hole in time. It wears a mask. We know that awful things happened—suffering, death, depression, despair—but we can’t quite recognize what they meant yet as history. Fragments are everywhere like phantoms haunting us, yet the semantic whole remains missing. We plant flags for the dead, but all they do is flicker in the wind. There is memory, but no taste or smell to it.

For a period when sensations themselves became but memories, what will it mean to establish connections back to its sensations? What was this lived experience of the world dying? What historical or memorial seance will make contact with a history of when we went contactless?

Particularly love that last sentence.

Thanks for reading. It took me a year to try to put into words that experience. Of course, for those who lost someone close, maybe what I write is a bit glib. It’s about surviving Covid, but for millions of people, way more trauma, things that might feel unspeakable for the grief they contain in blazingly clear memories, nothing murky or blank about them.