on the significance of the 1966 trips festival.

Here are the text and images for a talk delivered at The 1960s Revisited Symposium @ the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco on Friday, 22 January 2016. Revised and updated with corrections on 03 February 2016.

“If I were to tell you that an event of major significance in the history of religion is going to take place in this City of Saint Francis this weekend, you would say, ‘You stayed out of work too long.’ So, in mid-January of 1966, wrote Lou Gottlieb, one-time Limelighter folkie and, for a brief time, a music columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle. Gottlieb would go on to found the famous Morningstar Commune in Sonoma County (which is currently, at least according to its Wikipedia page, up for sale by his heirs if anyone is interested in restarting it). In his colorful way, Gottlieb didn’t just stop with religion. He continued, “And if I were to tell you that an event of major significance in the history of the arts is going to take place simultaneously, you would pat my hand and say, ‘Drink this glass of warm milk slowly and try to get some rest.'” He even went on, in his most wonderfully ridiculous metaphor of all, to note that the event was technologically significant: “In his infinite wisdom,” wrote Gottlieb, “the Almighty is vouchsafing visions on certain people in our midst alongside which the rapturous transports of old Saint Theresa are but early Milton Berle Shows on a ten-inch screen.” What had been in black and white, in other words, was about to go Technicolor.

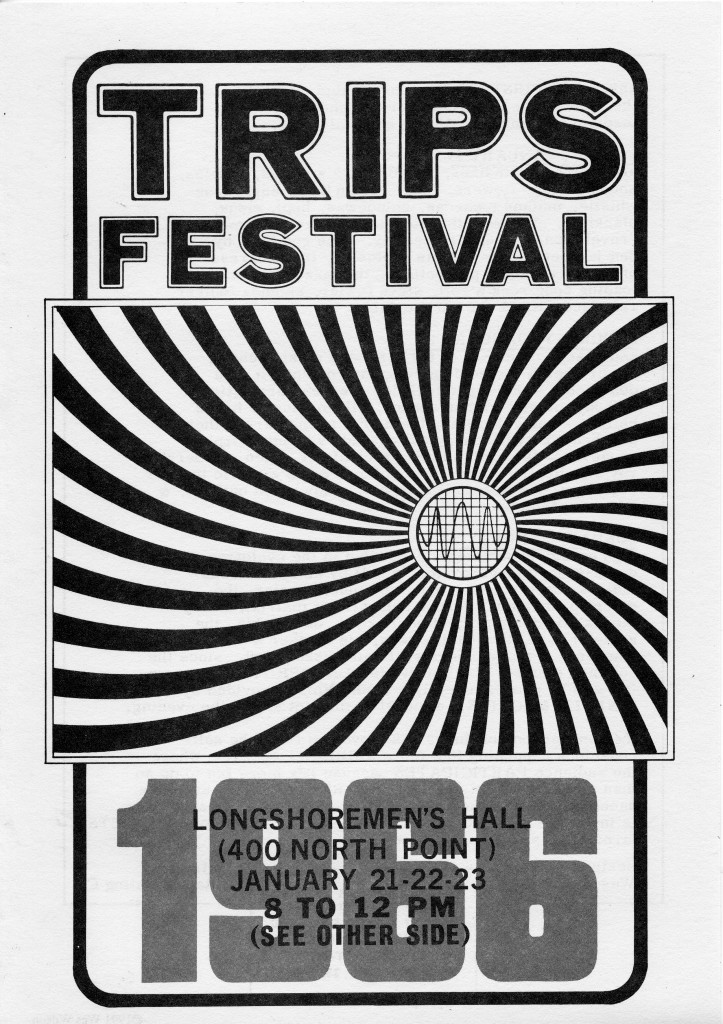

Gottlieb was, as you might guess, hyping the Trips Festival. He certainly thought it was going to be pretty significant. But what do we make of the event now, fifty years to the day from when it occurred? We might start to address that question with another preview of what was to occur that weekend, this time not in the purple prose of a hip Chronicle columnist, but in the evocative imagery of a graphic artist.

Wes Wilson’s Op-Art Trips Festival handbill pulls you in. Or does it spit you out? It’s a vortex. It’s a technological cave. It’s a broadcast signal. It’s a gyroscope. At its off-center center, there is a chart. It’s a radio frequency. It’s a Dow Jones ticker. It’s a brain wave reader. It’s an electrocardiogram for the heart. It’s a polygraph test.

In fact, it’s an oscilloscope, a device that plots out varying signal voltages. Whatever it is, it’s registering energy. The year 1966 is prominently featured in large gray letters at the bottom of the handbill. Everyone knew what year it was already. But the year matters. There is a sense of history present, intensified. This isn’t just an advertisement for a one-off weekend of fun. It’s an advertisement to be remembered. The image sends a message. The message is the medium.

The handbill is an entrance. Or is it an exit? Whether in the window of a shop on Haight Street in the early weeks of January 1966 or to the Chicken on a Unicycle website of historic San Francisco graphics in 2016, wherever Wes Wilson’s Trips Festival handbill, like the event it publicizes, travels, it is forever pinned to a threshold. It beckons us to step through its spiral, to come in from the cold to its pulsating electric core. But what is in there beyond that chart with the line racing up and down across it?

To be drawn in to the Trips Festival by Gottlieb’s hype or Wilson’s more cool, mysterious iconography, to want to see what’s there, to hope to join in, this was the key to the Trips Festival. It pulled people in to something alluring, different, strange, mysterious, potentially transformative. It announced that a path to the outside from mainstream, conformist, bureaucratic, alienating postwar America was available. It was, as Ben Van Meter titled his psychedelic film about the event, “an opening.”

How did this opening open up?

Inspired by the Acid Test parties that Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters had started putting on in 1965, The Trips Festival marked a moment when those anarchic, underground events got organized and went fully public. Not that the Trips Festival itself didn’t unleash a good dose of chaos into the world, too, but unlike previous nascent hippie events of the 60s San Francisco Renaissance, it offered more of a framework for weirdness to ensue.

It was organized by Prankster associate Stewart Brand, a onetime infantryman and parachutist in the US Army soon to be on a campaign to get a space-program photograph of the entire earth publicized, and from there to publish the Whole Earth Catalog and, from there, to go on to a lustrous career as a computer tech guru and iconoclastic ecological activist. Joining him were Ramon Sender, an avant-garde electronic music composer and co-founder of the San Francisco Tape Center, Roland Jaccoppeti, a photographer and actor involved with the Open Theater in Berkeley, and Zach Stewart, who along with Brand created a participatory, multimedia installation piece of teepees and slideshows called America Needs Indians. The Trips Festival eventually brought on the radical advertising activist Jerry Mander and then San Francisco Mime Troupe business manager Bill Graham to help pull off the event.

It was advertised as “an LSD experience without the LSD.” Acid was the subtext for the whole event. But while LSD was certainly to be had at the Trips Festival, the event suggested larger interests than just blowing your mind on drugs. The Trips Festival proposed that LSD and other hallucinogenic drugs were tools, technologies for probing new understandings of the self and society, individuality and community.

As Merry Prankster Carolyn Adams, Mountain Girl, puts it: “it’s really a mistake to try to qualify all this as ‘sex, drugs, and rock and roll.’ Because that’s not what was going on. What was going on was experimental communications of a whole new kind, using these new technological tools.” Could, she and the Trips Festival organizers wondered, the self be altered, improved, transcended, realized, through these technological engagements? What kinds of human being and human society were possible in the age of mass communications systems? What sorts of new communities and intersubjectivities could emerge in the on-off blasts of the strobe lights, within the flashing light shows and films spreading off the walls, in the amplified howls and tribal stomps of the rock bands, and through the circuitry of cables and microphones and speakers and public address system machinery that the Pranksters, along with LSD-chemist and all around bohemian alchemist Owsley “Bear” Stanley, brought to the affair? These were some big-time questions.

And then again, the Trips Festival was just a party—one weekend affair in the midst of the bustling mid-60s San Francisco Renaissance. And this too is what makes it important. For The Trips Festival did not occur in isolation. It became a key event, a coming out party, in a quickly accelerating line of transformative, adventurous, strange, places to be in the Bay Area in late 1965 and early 66.

The handbill tells us as much. This festival was going to take you on a trip, maybe one out of your skull and into the electro-techno-charged cosmos, but that trip had to start somewhere quotidian, some place concrete. In this case, it was a place literally made of concrete. As the handbill instructs, in smaller letters above the large grey 1966 numerals, the Trips Festival took place at the fairly new, modernist, concrete and copper, hexagonal-domed hiring hall of Harry Bridges’s ILWU, the Longshoreman’s Hall, down on Fisherman’s Wharf.

Built in 1958, the spaceship-looking Hall had served as the venue for the very first Family Dog rock music dances in 1965. Now it was 1966—January 21, 22, 23, from 8 to 12 pm to be precise—and those early rock dance events, “little séances” as Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh described them to Family Dog organizer Luria Castell when he came to attend one, seemed to be moving toward something more epic.

But what, exactly? Eric Christensen’s wonderful documentary film will let us enter the Trips Festival on those days fifty years ago to get a glimpse of what happened and give us details as to why and how it mattered. For now, I want to emphasize that we think of the event as a threshold, a moment of passage, a transition, a switch point. Beat giving way to hippie (Allen Ginsberg, pictured here, never actually showed up at the event, and this poster, according to most experts, is a fake, created after the event anyway, not for the Trips Festival itself), underground flowing up into the hyper-mediated spotlight, the membership of an insider’s club opening up its ranks rapidly, acid freak elite spreading out to a far broader, electrified audience.

Organized as what Brand calls a “contest,” it was an overlapping, a meeting ground, a liminal zone, what one reporter called an “electronic circus.” It was a coming together, a unification of bodies and spirits that mutated out in all kinds of new directions. It was a pulling in of people, ideas, and forces pulled together from a far-flung network of bohemian activity and pushed together through a psychedelic bottleneck, the genie let loose, unleashed into the open. It was, in its historical moment, an announcement of marginalized energies moving to the center of society, and, when the event was over, it had helped to fragment the center all to the edges. “Can you die to your corpses?” the Pranksters announced of their Acid Test portion in the Trips Festival program, “Can you metamorphose? Can you pass the twentieth century? “What is total dance?”

At the Trips Festival, we see older beatnik artsy modes of happenings and installation art dying to their corpses indeed, and what would become, with Bill Graham at the helm, the modern rock music concert industry, emerging. The psychedelic light shows are just getting going. They are still as much theatrical and visual arts experiments as a codified form of larger-than-life music concert spectacle and entertainment. Ron Boise’s Thunder Machines were present for people to bang around in, and Anna Halprin (about whose powerful work you can learn much more at the California Historical Society exhibition) and her San Francisco Dance Workshop ensemble members served as “kinetic catalysts” for the event, though from the looks of things, it didn’t take much to get people moving.

Much of the art, even the older bohemian stuff and certainly the acid-tinged futuristic-ecstatic elements, oriented itself toward frenetic, urgent, get out of your head and into your body participation. Certainly this was the ethos of the Merry Prankster’s Acid Test, of Boise’s Thunder Machines, of the light shows and rock bands too. Spectatorship was out. Participation was in. A circuit of crackling energy, in which selves and groups could explore the boundaries between internal and external, was the scenario to create, the milieu to foster, the activity to accentuate. You put on your mask to show your true self. Outside disguises of dazzling creative originality might allow for inside authenticity to emerge. Prankster Paul Foster wrapped himself up in gauze and tape like a mummy and hung a sign around his neck that read, “You’re in the Pepsi Generation and I’m a pimply freak.” For others, you frugged yourself silly to get away from inner demons. Or, like one young woman, you leapt on stage to strip off your shirt, pulling away the conventional costumes of everyday constraint to get natural and free. Inside coming outside, outsiders coming in under the spotlight. Across the increasingly permeable and playful line between inside and outside they went at the Trips Festival.

The event was set up to encourage this. The idea—one still with us in the current digital age—was that technology could help individuals and groups, and society as a whole, achieve participatory self-realization and collective liftoff to a better world. From the program: “This is the FIRST gathering of it’s kind anywhere. the TRIP—or electronic performance—is a new medium of communication & entertainment. the general tone of things has moved on from the self- conscious happening to a more JUBILANT occasion where the audience PARTICIPATES because it’s more fun to do so than not. maybe this is the ROCK REVOLUTION. audience dancing is an assumed part of all the shows, & the audience is invited to wear ECSTATIC DRESS & bring their own GADGETS (a. c. outlets will be provided).”

Indeed, this was much of what went on at the Trips Festival. Within Longshoreman’s Hall, society’s inside outsiders, those younger Bay Area baby boomers who were at once the inheritors of postwar American abundance and alienated outsiders to its halls of Vietnam War-escalating corrupt power, flooded in. The facts do get a bit murky though, and the legends and myths start to take over at this point. Publicity for the event brought anywhere between 6000 and 15000 attendees, from different accounts, and the event netted anywhere between $4000 and $12500 depending on whom you read. The line out the door of the Trips Festival lasted until 2 am each night, some report.

Inside, under the flags and banners hung from the rafters to lend the event an air of festivity and dampen the echo of all the buzzing amplifiers in the room, an outsider’s chaos broke loose. A new, unruly group was taking the reigns of hip, cool culture. As Jerry Garcia remembered: “It was like old home week. I met and saw everybody I had ever known. Every beatnik, every hippie, every coffeehouse hangout person from all over the state was there, all freshly psychedelicized.”

Trying to steer the proceedings somewhat, or to sail things off even “furthur,” as the destination sign on their infamous psychedelic bus put it, into the great beyond, the Pranksters constructed a control tower at the center of the affair. Ken Babbs stood at the insanely wired captain’s deck, narrating and navigating the affair like some wild combination of sports event color commentator and spaceship commander.

Meanwhile, even higher on the tower (at least according to Tom Wolfe’s account in The Electric Kool Aid-Acid Test), Ken Kesey hid out, disguised in a space helmet because he had been busted for marijuana possession earlier in the week, scrawled evocative phrases on acetate to project at massive scale on the walls of the hall: “Anyone who knows he is God go up on stage.” “The outside is inside, how does it look?”

A pre-Janis Joplin Big Brother and the Holding Company performed even though Prankster Babbs tried to stop them. But it was Garcia’s up-and-coming band, still known to insiders as the Warlocks or the house band for the Merry Pranksters, but now newly rechristened as the Grateful Dead, who stole the show.

At least according to some. They performed on both Saturday and Sunday nights, and, as Stewart Brand tells the story, it became clear that they were the winners of the Trips Festival. As Jerry Garcia tells the story, however, the Grateful Dead were too zonked on acid to perform at all. His memory of the event was that no one cared whether they played at all. “Everybody was just partying furiously. …It was a great, incredible scene and I was just wandering around. I had some sense that the Grateful Dead was supposed to play sometime maybe. But it really didn’t matter.”

At least it didn’t except to Bill Graham, who as the well-known tale goes, desperately attempted to put back together Garcia’s guitar after it fell apart so that the Dead could perform. “Here is this helpful stranger,” Garcia remembered fondly of the soon-to-be concert impresario.

Whether the Dead played or not, and from one quick shot in Ben Van Meter’s film about the event, it looks like they were on stage at least for a bit, the Trips Festival marked the start of something older ending and something new beginning: the divide between show and audience was crossed. On acid or in the electrified wavelengths of the Trips Festival, the theatrical fourth wall got smashed.

Here was something that took to the edge of anarchy what historian Fred Turner describes as a goal of certain influential mid-twentieth century American intellectuals: to use multimedia to concoct “democratic surrounds,” in which technology encouraged active, democratic engagement rather than passive, totalitarian helplessness among populations. The Trips Festival was a peculiarly California mode of doing so, an installment in what the great historian of modern California art-making Richard Candida Smith calls the effort to use personal experience to, as he writes, “redefine and expand the public order as a forum for exchange and perpetual revision of meaning.”

For Candida Smith, California artists pioneered the effort to render private revelation through artistic experience so that it could become “an arena where the imaginary could be put into flux so that people could repropose themselves, that is to say, repropose the relationships determining their position in society.” As Candida Smith’s puts it, “In this conception of social life, the arts, both popular and elite, become a primary form of collective governance, though one lacking any effective sanctions….” The Trips Festival was a kind of culmination of this ongoing California artistic effort to assemble a lose network of artists and bohemians into a new public life, a model for what democratic interaction in the technological age of mass communications could be.

Maybe that’s a bit grandiose for an event that placed a primacy on immediacy and fun. But grandiosity was certainly a part of the Trips Festival too. There was a politics lurking in the pleasure, really a psychedelic anarch0-syndicalism of a sort, a curiosity about creating environments for radical democratic pursuits that blurred the lines between friend and strangers, lovers and associates, a small band of pranksters and a whole society of hoped-for adventurers. A zany, loose feel of fictive kinship in the electronic pulsations of the modern American technoworld.

Putting it in less academic, world-historical terms, Chronicle music critic Ralph Gleason caught some of the more basic, surface-level energies taking place. “The truth about the Trips Festival is that it was a three-night, weekend-long dance with light effects. When the dull projections took over, it was nowhere. When the good rock music wailed, it was great.” The point was that people didn’t want to sit and watch. They wanted to interact, join in, play a part, get involved. They wanted to dance. They wanted to participate. They wanted to move across the line between inside and outside, insiders and outsiders. They didn’t want to only watch the show; they also wanted to be the show. It was, Bill Graham decided, “Living theater. Taking the music and the newborn visual arts and making it all available in a comfortable surrounding so it would be conducive to open expression.” What he glimpsed at the Trips Festival was that, in his words, “when all this truly worked, that space was magic.” And for him, “the key element was the public. Their reaction was the payoff.”

Of course, taking their money for putting on the event successfully was a payoff for Graham too, and this is what he would quickly gain notoriety for, and that was fine as well. But his and others’s understanding of the Trips Festival as an event at which private bohemia went public, outsiders came in, and insides were projected out through dance, multimedia, and participatory involvement, is telling. This was a gathering that saw some attempting to unleash individuality from the masses, self-expression from within the crowd.

There were limits to this pursuit of limitlessness, to be sure, whether they be of racial boundaries, gender norms, or cultural and economic differences of class. And there was the dangers of limitless too, a “whiff of danger” around the Pranksters that made even a close associate such as Stewart Brand wary. The whirling search for utopia had more ominous streaks shot through it—darkness as well light made the strobes flicker. But at an event that emphasized criss-crossing boundaries, moving outside inside and inside outside, there were also opportunities to try, at a level humming tentatively and awkwardly below all the ecstasy and pleasure, to address larger issues of social justice and equality.

Not that the Trips Festival’s program provided some kind of overt political manifesto. It was, through and through, just an arty party that turned into a crazed, immersive dance spectacle. But it also strove for beauty and connection between and among participants, through joining in around actions of individual creative flair and originality. It was about creating a system in which singularity and unity might arise simultaneously, across the boundary between coordination and improvisation, a self redefined and a collective coming together.

Within this radically pluralistic mix, to borrow a term that Nick Bromell borrows from William James to describe the effects of hallucinogenics and rock music that many young people experienced in the 1960s—within this setting that combined distinction with dissolution, assertion of self with a melding into something larger—we see glimpses, in the strobes, of social change occurring.

Individuals—young women, for instance—grabbing opportunities to stretch themselves toward new, less constrained modes of public presence. Men and women reached out to each other in ways that brought old and new modes of courtship together in search of communion. And in one amazing photograph snapped by Gene Anthony, a young man arrives in cross dress, a reminder that the gender politics of the counterculture were more complex than the typical (and yes, still mostly correct) portrayal of it as a hyper-macho affair. There was always a queer side to the counterculture, and a nascent queer politics in its tweaked rejection of normalcy and norms.

In all these ways, the Trips Festival’s point, its significance, was to amplify and intensify this effort to probe the possibilities of participation: of dissolving boundaries of inside and outside, the movie and the world beyond the frame, the show and the spectators, art and life itself. This is what made it part of a deeper tradition of avant-garde modernism, a cultural installment of the 1960s search for participatory democracy fully realized, and also, in its strange pastiche of high and low art, improvised tableau vivants and psychedelicized noisy white-boy versions of rhythm and blues, carnivalesque circus festivity and serious interpersonal questing, something futuristically sci-fi postmodern.

“It had that acid edge to it,” Ken Kesey remarked years later, “Which is, ‘this is something that might count.'” Its point was, as Ben Van Meter lyrically puts it, “no point.” “And I don’t mean pointless,” he goes on to say at a roundtable that is included on the DVD of Eric Christensen’s film, which we are about to see. “I mean it in the Zen sense.” For Van Meter and for others, the Trips Festival immersed participants in a transformative experience of connection that they could draw upon forever after. It did so sensorially, affectively, artistically, politically, ethically, morally. When a young person at the Trips Festival, in Van Meter’s phrasing, “reaches out his hand and looks at it and it becomes difficult for him to tell where the point is that he ends and everything else begins,” that’s when, according to Van Meter, “he’s got a moment of enlightenment there that will come back to him the rest of his life, periodically, because he realizes there is no point where he ends and everything else begins.”

And so the Trip Festival ended, fifty years ago. And with it, a certain era of Bay Area bohemia ended too, as another era, a far more mass-mediated spectacle on the Summer of Love national and international stage, began. In between, on those three nights, people partied, furiously, pleasurably softening the lines between self and strangers, and doing so in a sometimes harsh psychedelic maelstrom of technologically augmented experience.

It’s worth lagging with them for a moment, blurry as they are, on those nights in Longshoreman’s Hall, to listen and look in on what they did, to tune in historically to the Merry Pranksters’s lag system of tape delay sound reproduction equipment, which we can still, perhaps, faintly hear echoing its delirious and sometimes brilliant incantations into the present. Let us lag there so that we too might remind ourselves of our own immersions in the contemporary world of mediated collectivity—with all its alienations and, so too, its possibilities. So that we too might strive, both alone and together, to frug and vibe, feel and talk, dance and think, act and interact, our way to something better.

the ginsberg poster is not contemporaneous with the trips festival and was printed at a later unknown date

Is that really true?! I always thought it was printed as part of the publicity leading up to the weekend! Do you know anything more about its story?

The “Acid Test poster with Allen Ginsberg” reproduced in the present article is a known fake. (Poster has been removed.) Story located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acid_Tests

According to the section “Posters & Ads” on the Ken Kesey & the Merry Pranksters website http://www.lysergia.com/MerryPranksters/MerryPranksters_main.htm, the poster with caption “Acid Test poster with Allen Ginsberg,” reproduced in this article (Acid Tests) is a fake.

The above referred to page (KEN KESEY & THE MERRY PRANKSTERS) states the following regarding the poster: “This poster with Allen Ginsberg, supposedly promoting day 2 (the Acid Test) of the Trips Festival, is fake and recently manufactured.”

Also telling is the fact that none of the auction houses I could find that deal with actual original/vintage posters, handbills, etc., are looking for or carry this. It does appear for sale in places like eBay, amazon, etc., typically with no details a out provenance

The boxing poster design does not fit with the other materials for the festival.

I don’t know when and who created this poster.

If I were a betting man. . .

Concerning:

“Trying to steer the proceedings somewhat, or to sail things off even further into the great beyond, the Pranksters constructed a control tower at the center of the affair. Ken Babbs stood at the insanely wired captain’s deck, narrating and commenting the affair, like some wild combination of sports event color commentator and spaceship commander.”

Certainly a spaceship commander given:

Ken Babbs, one of the Merry Pranksters, saw firsthand the lifting power in the Grateful Dead’s music during the group’s stint with the Acid Tests, saying: “We always thought of the Grateful Dead as being the engine that was driving the spaceship that we were traveling on[. . .]Once the Grateful Dead got the engine cooked up and running that became the motor driving the thing. It provided something that kept everything going.”

To take these trips, the participants had to be like “astronauts of inner space. We had to be as well-trained, in as good a shape, and as mentally powerful as an astronaut in outer space so as not to be thrown by any of the accidents or the unexpected we’d run into,” he said.

Babbs’ colleague Ken Kesey used the same space age metaphors to describe the Grateful Dead: “I saw them as the main afterburner of a spaceship that was going to leave this dimension.” That afterburner was powered by “audio rocket fuel” the basis of which existed in the Dead’s unique blending of musical styles that included folk, blues, country, electronic, bluegrass, rhythm and blues, jazz, and rock ’n’ roll.” He also called the Dead “the faster than light drive.”

But that’s all part of another metaphor.

BTW I think it’s an oscilloscope.

That’s about it, says the man who one day will proudly become Jerry Mander

regarding this poster:

http://ww1.prweb.com/prfiles/2012/01/27/9145727/gI_99649_grateful_dead_trips.jpg

check dates on it — for an april event

Harry B,

Yes, Jesse Jarnow told me Phil Lesh described this somewhere as a “knock off” Acid Test in April 1966. There is even a radio spot for it: http://freeform-radio.blogspot.com/2016/01/trips-festival-1966-radio-promo.html.

I love the ? on that 196? April Trips poster.

Where is the radio promo?

http://freeform-radio.blogspot.com/2016/01/trips-festival-1966-radio-promo.html.

“Sorry, the page you were looking for in this blog does not exist”

Looks like whoever put it online took it down.