listen to this: what would it be like to hear an image’s data to understand more vividly what the image represents?

For twenty-five centuries, Western knowledge has tried to look upon the world. It has failed to understand that the world is not for the beholding. It is for hearing. It is not legible, but audible.

— Jacques Attali, Noise: The Political Economy of Music

What would it be like to hear an image?

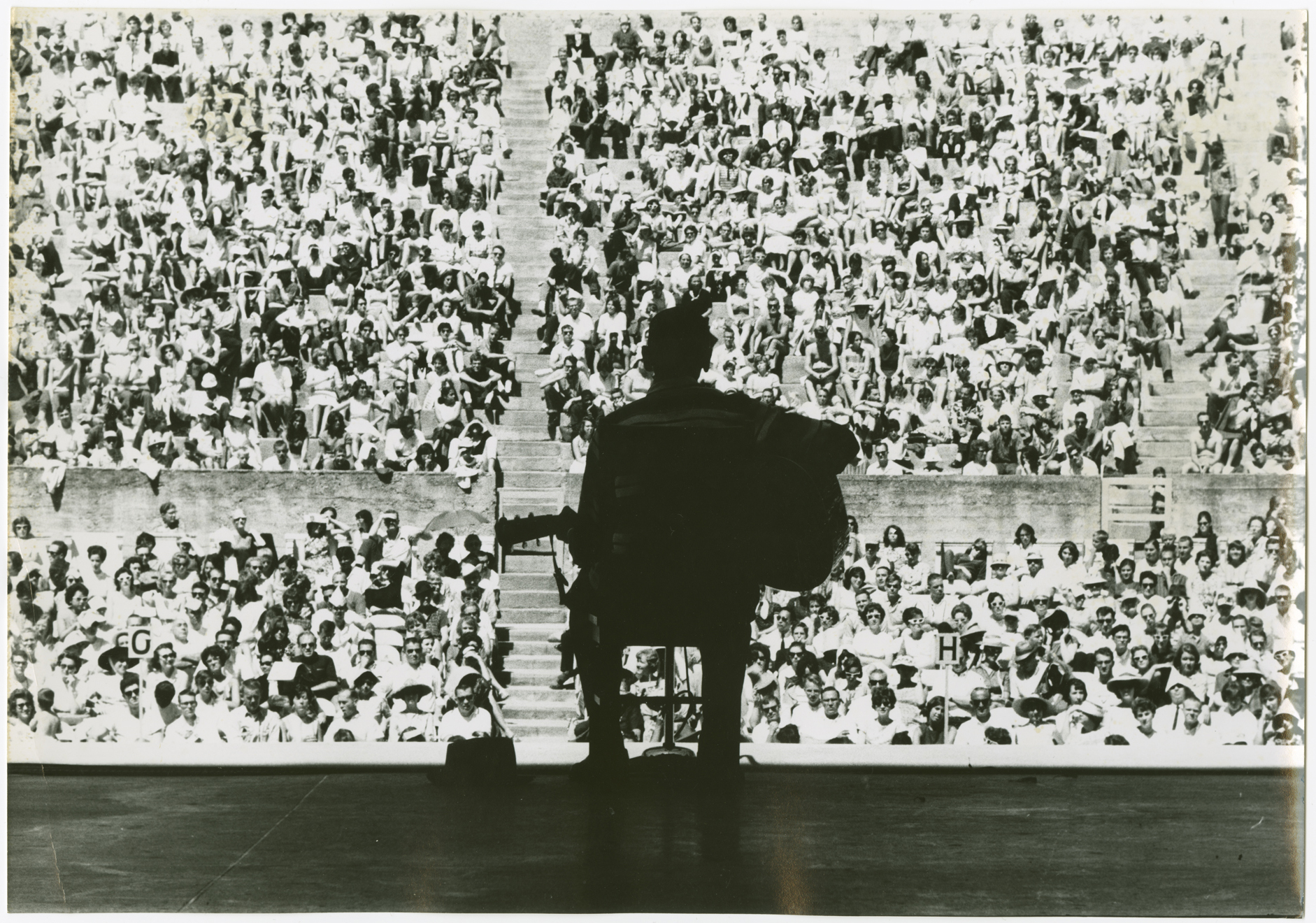

One of the great treasures of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection is its collection of photographs. My students are always drawn to these, not only because they provide access to performers that they may know (at least vaguely), but also because they offer many tantalizing glimpses of the audience.

As I go through the archive myself, I am struck at the irony that this sound-filled event is represented most of all by images—powerful and evocative images to be sure, but silent ones nonetheless. We do have a bit of audio, and there are more sound recordings to gather together from the Smithsonian Institution and other archives. There were even concert films of the 1967, 1969, and 1970 festivals, produced for public television station KQED. But these are now lost (if you have any leads on any copies of those television concert films, please get in touch with me!). Moreover, if one expands from Berkeley alone to folk music revival festivals in general, and if one then also includes the commercial and field recordings of various musical artists, then the amount of audio truly starts to develop a density of sound. This question of folk festival audio—and what to do with it—is high on my research agenda.

But those images keep drawing my attention. There are so many of them. And many of them are so good. If you look at them long enough, they almost seem to start to speak, to sing. The visual becomes audible—almost.

The digital humanities/history question becomes something like this: might the digital bring out the sounds of these photographs? Which is to say, once we begin to translate archival objects of all types into bits and bytes, can we do something synesthetic with the data? Could we, for instance, translate the body language and physical spaces captured in the photographs into sonic equivalents? Could we bring together existing audio recordings with the visual evidence in provocative ways through correlation or even discordance? How, overall, might we use the digital to explore the making of sound by looking more closely at its production?

In short, there has been so much work on digital visualization studies, what about digital sonification studies?

*Hat tip to Mary Caton Lingold of Duke University’s SoundBox Project for correspondence that inspired this post.