using the spreadsheet to connect evidence to argument.

For most humanists, looking at spreadsheets makes their eyes glaze over. There is even an ominous sense of imprisonment: one must literally put ideas into cell blocks. The database would seem to limit the subtlety and dexterity of humanistic analysis in problematic ways. It insists on squeezing the messy realities of life, ideas, emotions, practices, art, and expression into neat rows and columns. Metaphorically speaking, we go from the diverse architecture, natural topography, and even entropy of the world to a system of standardization: from undulating hills, inventive buildings, and people in all their strangeness to parking lots, faceless office towers, and cubicles of corporate capitalism in its most terrifying structural forms. Everything must fit, regardless of its size, shape, inner dimensions, or odd configurations. Standard deviation is allowed, but not just plain old deviation, and certainly not deviance. Such is the age of “big data” in its most troublesome dimensions.

But what if the table could be put to use for humanistic analysis? Developing “good” data can undergird new searches for patterns, visualization, and algorithmic analysis. But there is an additional way that tables might be useful: not as the platform for statistical manipulation or coded patterning, but as a bridge between evidence and argument.

This is a simpler—deceptively simpler—use of the table, one that seeks to move beyond the drift toward positivist dreams found in the use of big data systems analysis for digital humanities.

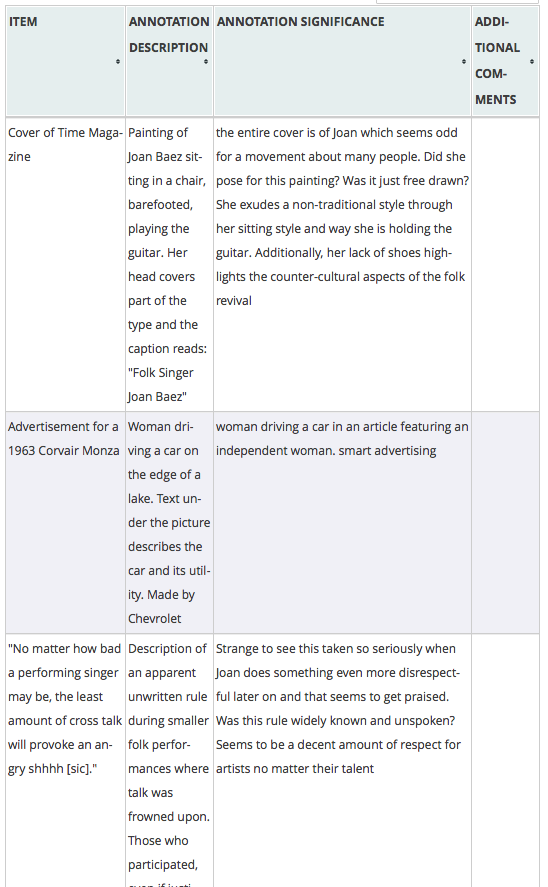

In my Digitizing Folk Music History course (related posts and notes here), students used the WordPress plugin WP-Table Reloaded not only as the underlying structure for computational operations to create visualizations, maps, and other representations of information, but also as a link between evidence and argument. The table became a notetaking device, a way to make annotations and comments about digitized text, image, sound, and video and start to turn these detailed observations into a larger interpretation. The table became a vehicle for transitioning from evidence to what to make of that evidence. First, it took the student more deeply into the object being scrutinized. Then, in bringing the student more deeply into engagement with evidence, the table sent out a structure—a pathway—for the student to step up as they reached toward a more nuanced assessment.

Working with tables, students (you could write researchers here too) were not merely writing metadata of a digital collection in the strict sense: they were developing an extended line of meta-metadata that was transitioning out from the evidence to analysis. Supporting this process, the table served (fittingly for its shape) as a crucial building block. It was situated at that mysterious point between discoveries and findings, observations and conclusions.

It is this space, I believe, where digital humanists truly have something to contribute to the interdisciplinary study of the world. But without more focus on this area, the field risks becoming merely a subset of computer science. The question is: how might the digital enhance the step from a body of evidence to an interpretation that places that evidence in conversation with existing arguments and interpretations?

In Digitizing Folk Music History, placing object-annotated entries into tables forced students to look, listen, feel, and sense more intensely, more closely, and with more awareness. They then had to pinpoint, to notice, and—crucially—to begin to explain. The spreadsheet’s rows and columns started to become a kind of ladder that they could climb up from evidence to interpretation.

This was not macro-analysis or big data or quantitative work. It was closer to qualitative micro-analysis or what we might even call “small data.” It is something, of course, that the humanities excels at: a sensitivity to assumptions about scale and an insistence that more information does not necessarily equal more truth. When it comes to humanistic understanding, the smallest element might turn out to be, interpretively speaking, “bigger.” Which is to say it might, at times, perhaps even quite often, be more telling, more important, more significant than the overview of a mass of data.

To be sure, masses of data are good. Lots of data organized in usefully systemized ways and analyzed using the tools of statistics and other more quantitative approaches are worth the time of humanities scholars. But these should not be the sum total of digital humanities and its potential uses of the database, spreadsheet, and table. To restrict the digital humanities to the quantitative use of data alone is to reproduce very troubling technocratic interpretive moves dominating our society right now: various kinds of flawed educational testing and evaluative methods, for instance, which substitute a shallow, smoothed-out, bird’s-eye view while neglecting an awareness of the variegated richness of human experience and knowledge in closeup perspective. In particular, they threaten to omit what I would call the vernacular, everyday dimensions of being, the things that occur below and beyond the radar of top-down power and the structures of control. Or better put, certain modes of quantitive analysis have the risk of vacuuming these important aspects of human life into the vacuous digital machine. The results might be cleaner, more efficient, more totalizing; they would also be wrong, or better put, not the whole story.

The use of digital tables only for tabulation, only for big data and not also for small data creates a framework in which the digital humanities might dehumanize rather than expand humanistic endeavors. To phrase this point as a question: how can we database the digital humanities without debasing it?

Putting this larger moral and ethical dilemma aside—or, more accurately, addressing it at a in practice—the task for the digital humanities, and it is a challenging one, is to remain aware of the uncertain, varied, unruly terrain of human existence even as that existence gets represented in digital form. How, we might ask, can we develop more powerful understandings of our unstandardized existence using the standardized forms of the database, the spreadsheet, and even, of course, the digital itself (which after all turns analog signals into ones and zeroes, bits and bytes, therefore leaving out details—think of the famous case of the mp3 file, which omits parts of the analog sound wave, much to Neil Young’s dismay)? After all, the tools of the digital allow us to zoom in as well as zoom out. It is how we do this zooming that will matter in the long term. The question is not how to “scale” the humanities up, but rather how we will put the challenge of scaling the humanities up on the scales of humanistic inquiry.

My position is that leaving out the micro-level ways in which the spreadsheet, database, or table can connect evidence to argument undermines the full range of how the digital humanities might expand, improve, even transform humanistic scholarship. In my research and teaching thus far, what I have been most struck by is how the digital can, potentially, enhance the strange, mysterious, almost mystical transit point between evidence and argument, between the materials we marshal for an argument and the little leap that happens when we, databases and processing machines of a sort ourselves, schematize and systematize those materials into an argument that is in productive conversation with existing interpretations.

I agree, and I think your position is a very sensible one. And yet “putting this larger moral and ethical dilemma aside, or, more accurately, addressing it at a practical level” is also a very good description of the main and most potentially damaging intellectual shortcoming of digital humanities practice, in its profound practical *busyness.* One cannot set such dilemmas aside, or reduce them to practical problems, if digital humanities is to avoid becoming a form of dehumanization.

Brian — Thanks for your comment. I agree. I would venture something like the following: practice must be infused with theoretical awareness—deep ethical and abstract study of the stakes of the digital; this theoretical awareness, however, can be deepened by experiences of practice—getting into the tools and their uses in specific instances. Let’s throw in a bit of poesis too, while we’re at it: we can make things with DH, we can create new ideas too, but the goal is also to make good things and create good ideas. The trick, I think, will be to be “busy,” as you critically put it, but in such a way that it enhances contemplation rather than drowning out thinking. I think Adeline Koh’s explorations of these issues are quite provocative: http://www.adelinekoh.org/blog/2012/05/21/more-hack-less-yack-modularity-theory-and-habitus-in-the-digital-humanities/. — Michael