artifictions for artifacts? digital deformance as a mode of historical inquiry.

Digital history’s promise is not big. By which I mean that the potential of the field is not ultimately to be found in big data, big scale, big history, or the return to cliometrics or a computational mode of the longue durée (or as spellcheck would have me write it, the tongue puree). Rather, the promise of digital history is the convergence of artifacts into the pliable, ductile, mutable form of digital code. The ability to go big is really just a subset of this larger shift in the materiality of things from which we construct historical interpretation and narrative. Cliometric, statistical, and big data approaches are simply a few of the potentially productive “deformances” enabled by the convergence of artifacts into digital data.

In Digitizing Folk Music History, a research seminar I teach at Northwestern University, students and I combine Trevor Owens’s wonderful assignment in critically addressing “screen essentialism” (“Glitching Files for Understanding: Avoiding Screen Essentialism in Three Easy Steps,” The Signal: Digital Preservation, 5 November 2012) with the techniques of “deformance.” The goal is to adapt these efforts to practices of historical inquiry. We do so both in relation to studying the history of the US folk music revival and to think more creatively about what history is, exactly.

It may seem odd to glitch and deform—perhaps even to distort—artifacts in service of seeking deeper truths about a particular historical topic and historical method and practice in general, but it is precisely in “messing” with our artifacts that my students and I found ways to understand them more deeply as constitutive elements of—or better said, perhaps, representational lenses through which to view and make sense of—the folk revival story as well as the larger stakes of historical method as a whole.

What is deformance?

In Digitizing Folk Music History, we concentrate on digital image files (and sometimes sound files) because the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, our core archive, contains such rich photographic documentation (we are, of course, also concerned with musical and sonic history). Deformance, however, first surfaced primarily around textual analysis. What is deformance? As Mark Sample has written, the term is “a portmanteau that combines the words performance and deform into an interpretative concept premised upon deliberately misreading a text, for example, reading a poem backwards line-by-line” (“Notes towards a Deformed Humanities,” Samplereality, 2 May 2012). Deformance intersects with older operations that turn to stochastic methods in order to examine texts from new angles: everything from Emily Dickinson’s tantalizing concept of Backward Reading to Randall McLeod’s “transformissive reading” to the systematic word-substitution tactics of the Oulipo group. Moving beyond text alone, one might also include the Zen-inflected compositional ideas of John Cage or the choreographic approaches of Merce Cunningham. To be sure, the influence of Dada, Surrealism, and Situationism lurks in deformance as well.

As an influential article from 1999 on “Deformance and Interpretation,” Jerome McGann and Lisa Samuels contended that:

A deformative procedure puts the reader in a highly idiosyncratic relation to the work. This consequence could scarcely be avoided, since deformance sends both reader and work through the textual looking glass. On that other side customary rules are not completely short-circuited, but they are held in abeyance, to be chosen among (there are many systems of rules), to be followed or not as one decides. Deformative moves reinvestigate the terms in which critical commentary will be undertaken. Not the least significant consequence, as will be seen, is the dramatic exposure of subjectivity as a live and highly informative option of interpretive commentary, if not indeed one of its essential features [my italics].

Another digital literary scholar, Stephen Ramsay, puts it this way:

The notion of ‘deformance’ provides the critical framework for a discussion of conventional criticism as an activity dependent upon the notions of constraint, procedure, and alternative formation. It is in this light that computationally enacted textual transformations reveal themselves most clearly as self-consciously extreme forms of those hermeneutical procedures found in all interpretive acts [my italics].

These literary scholars make use of computational transformations of literary texts in service of accessing the underlying meanings, logics, possibilities, dimensions of the original publications. Paying attention to textual composition through computer-generated operations of recomposition, they remix to attend to the qualities of the original track. Recoding, in these critical and analytic methods, has a way of helping us decode.

Recoding and decoding also link to the question of digital encoding because the particular kinds of deformances one can do with computers necessarily rely on the ways in which these machines can remediate and reproduce many outputs from a shared basis in binary code. What you see on the screen—the interface—is, in its own strange way, really just another deformance, another representation that transfers machine-readable language to a human-decipherable graphical user interface. What we’re looking at isn’t really what we’re looking at. Even “code” itself is this: a “deformance” of the underlying bits and bytes of binary processing. At root, we’re dealing with on and off electronic pulsations organized into patterns. We “deform” these to make human sense of them. To make use of computation, we must pretend we’re looking at something essential. It’s a good reminder, however, to remember that we are not. Or, as Trevor Owens puts it:

New media and digital humanities scholars have coined the phrase “screen essentialism” to refer to a problem in many scholarly approaches to studying digital objects. The heart of the critique is that digital objects aren’t just what they appear to be when they are rendered by a particular piece of software in a particular configuration. They are, at their core, bits of encoded information on media. While that encoded information may have one particular intended kind of software to read or present the information we can learn about the encoded information in the object by ignoring how we are supposed to read it. We can change a file extension and read against the intended way of viewing the object [my italics].

Deformance for historical inquiry

In Digitizing Folk Music History, students use Owens’s instructions to explore images from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival (and sometimes with sound). At first, they are dubious (a few stay dubious): how could seemingly random messing with the underlying code of artifacts do anything but produce cool glitchy art? How could it lead to new perspectives or interpretations of the past? But the disorientations and chance operations of deformance and glitching have a way of helping them see history more precisely. The bending but not totally breaking of evidence catapults them toward new glimpses of the materials themselves as well as their movement through time, through history.

“A nice metaphor for the folk process itself”

“I found that deformation helped me see the photographs/images in different ways,” student Alistair Murray wrote. “If I find myself at a loss for words in describing or analyzing a photo, I think deforming it might shed light on the various meanings of the original image.” “I would agree with you that I think deforming an image is helpful as a tool of analysis,” concurred student Lily Orlan in a comment on Murray’s post. “Deformation,” Murray added, “might also be a nice metaphor for the folk process itself and the constant shifting, splicing, transformation of culture” (my italics).

“The importance of image and persona in the folk revival”

“I found this assignment to be unique in this field of study,” student Camille Micholetti observed. “While the historical archival process is primarily centered around preservation of original form, this exercise was focused on purposeful changes being made to an artifact. I don’t know anything about code so my edits to the image I chose were done completely at random; however, I believe they reveal some interesting information about this photograph of Joan Baez.”

For Micholetti:

The most compelling result I found after generating the deleted code version and the copy/paste edit of the photo was the inverse relationship the images had with each other. The former keeps most of the singer’s iconic image intact but renders her name and the publishing information at the bottom illegible. Conversely, the latter reveals her name but warps her face, making her much less recognizable based only on her appearance. These observations led me to contemplate the importance of image and persona in the folk revival—what aspect of the performer’s identity was easier to recognize and associate with her talent, her name or her appearance? For a singer as iconic in both name and appearance as Joan Baez, it’s hard to determine [my italics].

“Brought my attention to the ring that she is wearing”

Kristen Campbell also chose to focus on Baez. Her deformance led her to notice new details in the original photograph as well. “I do think that the experiment helped me see the image in a slightly different light. The way that the lines frame Baez’s face and hand is really interesting and brought my attention to the ring that she is wearing—a detail that I had largely glossed over before.”

“a veritable synesthesia of folk music”

Jack Wiefels brought us to a different scale of imagery from the Berkeley collection with his focus on a backstage shot of Doc Watson performing in the Greek Amphitheater on the Cal campus at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

“After perusing through the BFMF photo archives I came across a picture of Doc Watson that caught my eye,” Wiefels wrote. “The picture in itself already seems iconic—here blind Watson sits, alone on a stage in front of thousands of onlookers, yet appears ready to impart something intimate to the audience.” For Wiefels, the code deformances reinforced his sense of the folk process. “As I began editing the text on the picture, technicolor lines started to appear. This effect reinforced the notion of folksong as artform for me. Though supposedly ‘traditional’ in nature, folk tunes allow musicians to personally paint their own vision of their culture (or of a culture that they identify with) as it uniquely resonates with them.”

Wiefels decided that:

This helped me solidify my view that folksongs should be malleable forms, for if they were performed in the same way (or style) across generations, they would quickly lose their appeal. Ironically, my deformance highlighted this thematic element by focusing on a blind performer. Watson consistently reinterpreted and adapted…folk tunes. In doing so, he created a veritable synesthesia of folk music, arguably connecting a broader base of people to folk because of this. Folk music could have stayed black and white, but it’s much more interesting in color [my italics].

“The thematic observation from the original photo became clearer—to me—through visual distortion”

Moving into the technicolor future, Julia Popham left the Berkeley archive to look at an image from the 2007 Seeger Family Tribute celebration at the Library of Congress.

“After browsing through a collection of photographs taken from a 2007 ‘Seeger Family Tribute’ celebration,” Popham explained:

I selected one of Pete Seeger leading a ‘Des Colores’ sing-along. I was drawn to how the photograph portrayed Seeger—an old man rooted in lifelong, consistent, musical principles. Unlike Bob Dylan who became disillusioned with the folk’s ideological vision, Seeger remained firm in his music-based, humanitarian vision. In the original photo, I especially liked how Seeger and an audience member/singer looked at one another while singing. As the group is composed in a half circle, I felt like the eye-contact completed the distance—making the group of singers look like a united front (pun intended). In the second photo, in which I deleted a chunk of information, this ‘united front’ perspective became even more acute. The faces and bodies were cut and merged, uniting the singers into one entity, one soul. Yet what struck me the most was how Pete Seeger and the woman continued to hold eye-contact. The merged faces/bodies and consistent eye-contact further solidified Seeger’s vision to unite people through music. To my surprise, the thematic observation from the original photo became clearer—to me—through visual distortion. I was quite baffled by how a thought/observation could develop through random alteration. The process unveils a strange interaction between randomness and meaning, entropy, and consistency [my italics].

In a comment on Popham’s deformances, fellow student Melissa Codd added an additional acute observation about the significance of Seeger’s banjo:

Even through the damages of glitch, Seeger remained the leading figure or conductor of the musical activities in the photograph. However, I think it is interesting how his banjo moved away from him. He remained firm in his position so he was not able to keep up with the changes in the folk revival. In the second glitch (the one with the deletion) it seems like the younger people are out of his reach…they are in the glitch. He can not really lead him especially without his banjo [my italics].

“A new interpretation of the second folk revival of the mid-twentieth century”

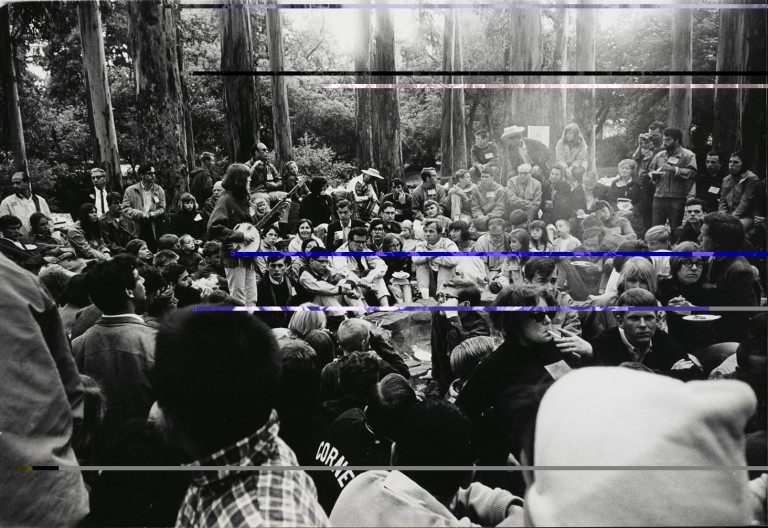

Ross Jordan took an image of Alice Stuart performing at a Berkeley Folk Music Festival campfire to contemplate both the material quality of digital artifacts and, from there, to consider his glitches images more directly in terms of what they suggested about folk revival ideals of community and individuality.

“I think this assignment shows that deforming evidence can definitely lead to historical insights, especially unintentionally,” Jordan concluded:

One of the advantages that digital data has over traditional, physical methods of storing information is that you can store huge amounts of information extremely efficiently. However, just as physical historical sources (like letters and newspapers) deteriorate over time, so too does digital information. Hard drives and CD’s have limited data lifespans, and eventually this data will become deformed. I’m not sure whether this process will yield the same results as the changes we made to the code of image files, but given the vast amount of information stored digitally, historians in the future might have to deal with corrupted data like the ‘glitched’ image files, which could lead to new interpretations and meanings of primary sources.

For example, in the file I glitched, I deleted a chunk of code near the bottom of the txt file, and this completely erased a large section of the bottom of the picture. Whereas in the original image there is a large group of young people gathered around in a ‘folk circle,’ in the altered image the front half of the circle is erased and the gathering now resembles a more traditional performance. This might offer a new interpretation of the second folk revival of the mid-twentieth century. One of the major themes of this second revival seems to be a rejection of postwar society in favor of a return to the collectivist social values of the 1920s and 30s. However, looking at the altered image could make us turn away from the themes of collectivism and progressiveness, but instead focus on individual and personal motivations for young people having a newfound interest in folk culture [my italics].

“Your observation that Leadbelly is drowning in a time more modern than his own, reminds me of a Warhol in a funny way”

Student Ellery Stritzinger made connections between her deformance experiments and studies she is pursuing in computer science when she glitches an image of Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter.

Stritzinger wrote, “I really really enjoyed seeing the mechanics of a digital image. As I learned in EECS last quarter, code is perplexing and usually not respond the way one may expect. The fourth image is one in which I inserted code from another photo, hoping that the two would create some sort of collage, but instead created only a more extreme version of removing code from an image as in the previous two. I interpreted these changes in the photos as history and chronicles of the past drowning in the chaos of modern technology. I imagine Leadbelly would be baffled at the transformation” [my italics].

Perhaps he would have been, although Leadbelly might also have taken his place alongside other artists of the twentieth century in glimpsing Stritzinger’s glitches. Such as Andy Warhol. As fellow student Camille Michelotti wrote to Stritzinger:

I really love your last version of this picture. The bright and contrasting colors that splash the classic photograph, along with your observation that Leadbelly is drowning in a time more modern than his own, reminds me of a Warhol in a funny way. Interestingly enough, Warhol executed his own sort of deformance in his art, using silk screening to reproduce iconic images repeatedly with a pop twist in bright colors. Additionally, he produced these prints in a modern, assembly-line fashion. This is a great example of the way historical photographs can be repurposed, much like the way traditional folk songs were and continue to be repurposed by new generations of performers [my italics].

As Michelotti notes, Leadbelly’s traditional folk music approach has fascinating parallels with Warhol’s interest in where the technological and handmade, the duplicated and the singular, collided. Leadbelly as Pop artist! Warhol as folk painter!

“Deforming my chosen image of Dylan served to emphasize certain aspects of the album cover that I hadn’t noticed before”

Lily Orlan turned to another figure who raises questions about where folk and Pop collide: Bob Dylan. “I chose to deform Dylan’s The Times They Are A- Changin’ album cover,” she wrote, “largely because it’s one of my favorites of his. I also really like the image of Dylan on the cover—I think his facial expression is really interesting because it conveys a sense of contemplation from the artist, and that’s an emotion that I feel has a strong presence whenever I listen to Dylan’s music. I also figured there would be a lot to work with in this image, because it contains both a close up photo of Dylan’s face, as well as a track list for the album.”

“After deleting a few lines of code, the color of the image changed a little, transforming from black and white on top of a distinctly rustic yellow to more of a dark purple/ black and white,” Orlan explained. “This immediately gave the album cover a more somber, darker tone, and emphasized the aforementioned contemplative vibe that I got from Dylan’s facial expression. It also blacked out the lower portion of the album cover, placing more emphasis on the upper half of the image, and thus on the Album name and track list, as well as on Dylan’s eyes.”

“In the second deformed image,” Orlan continued:

in which I pasted additional code, the album cover turned a bright purple, giving it an almost surreal essence. The coolest part of the second deformed image is that it split up Dylan’s face, and specifically cut out the horizontal plane that contains his eyes, shifting them slightly and ‘deforming’ the entirety of Dylan’s face in the process. This was probably my favorite aspect of the entire project; as mentioned earlier, Dylan’s facial expression was one of the reasons I chose to deform this image in the first place, and this second deformation specifically highlights the artist’s unique facial expression by emphasizing his side-cast eyes and raised eyebrows. …The second deformation also pixelated Dylan’s name, seemingly calling into question his intended identity in releasing the album.

For Orlan:

In light of the observations I just made, I think that the experience of ‘deforming’ an object can actually be really helpful in terms of thinking about archival material in a new way, as well as leading to new historical insights. What I found was that deforming my chosen image of Dylan served to emphasize certain aspects of the album cover that I hadn’t noticed before—for example, the artist’s side-cast eyes, and how the yellowish background served to set a specific mood for the album. In deforming the image, these important aspects were either changed or altered, and noticing their changes served to emphasize for me what the original image was intending to convey. Thus, I think new historical insights, particularly regarding the intended purpose of archived images, can definitely be achieved through the process of deformation [my italics].

“By manipulating the original recording of ‘Tangled Up In Blue,’ I felt a valuable opportunity to reconsider my relationship with the song”

Finally, Tanner Howard took us into an entirely different vantage point on Dylan by shifting from the visual to the sonic for his deformance. “I decided to take a different approach,” he explained. “I recently learned from a friend about the possibility of editing an mp3 file in Photoshop by converting it into a RAW image file. Just as a jpg can be turned into a txt file and then be manipulated in a text editor, this approach gives one a little more tactile, playful ability to manipulate pure code in a very different manner.”

Tanner began with an mp3 version of Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up In Blue” from Blood on the Tracks (Columbia Records, 1975, see below). “From the original mp3,” he wrote, “it’s possible for one to change the file extension from mp3 to raw and export it for manipulation into Photoshop.”

Then, Tanner manipulated the source code visually, using the eraser tool in Photoshop:

Using the erase tool, one can literally manipulate the song’s source code on a visual level, then turn it back into song form after exporting it as an image and changing the extension back to mp3. I did two different passes of this experiment [see below]. Both are borderline unlistenable, but I still felt it to be a valuable chance to reconsider what I consider one of the best folk songs of all time, one I have a particular history with. …On the second pass, I decided to be a little more tactful with my erasing, trying to be more focused in where I erased to see if I could determine a little more clearly the impacts of my behaviors.

Tanner connected his deformance experiment in Digitizing Folk Music History to “a media theory class [in which] we’ve discussed the experiences we have with new media and how they influence our lives.”

He wrote:

In my reading for this week’s class, author Mark B.N. Hansen described the disassociated relationship we have with the myriad types of digital media we encounter, arguing that these forms of media are the first in human history to be completely abstracted from our sensory experiences. In the chapter, he wrote, ‘What we see on the computer screen (or other interface) and hear on the digital player is not related by visible or sonic analogy to the data that is processed in the computer or digital device. Indeed, as the work of some digital media artists has shown, the same digital data can be output in different registers, yielding very different media experiences’ (Hansen, 179).

Tanner concluded that the glitching of “Tangled Up In Blue” gave him a new way of thinking about Dylan’s own “deformances” of the track over the many years the folk-rock icon has performed the song live:

By manipulating the original recording of ‘Tangled Up In Blue,’ I felt a valuable opportunity to reconsider my relationship with the song. Interestingly, my complaints about the slowed-down nature of Dylan’s live version were reversed by my digital efforts, as the track gleefully skips over itself, thanks to some aspect of my machinations manipulating the song’s tempo. My version of Dylan still sounded recognizably Dylan—and yet, it resulted in an iteration arguably further removed from the original version of the song than Dylan’s own live arrangement [my italics].

For Tanner, the deformance also helped him perceive more lasting aesthetic and historical accomplishments in Dylan’s music that the deformance, by distorting the track then returning it to its original form, brought to the surface. “Still,” he decided, “the closing seconds of my digitally processed version return to their proper form, a reminder that, buried beneath any changes, the source material will always endure, no matter what my digital editing or Dylan’s aged singing can do to the track.”

Conclusion

For Tanner, as for all my students, deformance and glitching helped them look and listen more closely. Their attention bore sophisticated interpretive fruit, both about the folk revival itself and the larger methods by which we perceive and make sense of artifacts and evidence to produce historical meaning. These tactics make use of the strange material qualities of digital code, of the interplay between the machine-readable and the human-readable, of the ability to “mess” with artifacts as they converge in the digital medium. For some historians, deformance and glitching might seem quite disconcerting, at their worst resembling something like Stalin airbrushing a Soviet official out of a photograph after sending him to the gulag. But if handled smartly as a new method, they can render history more revealing, more accurate, more illuminating.

We glitch for glimmers of truth lurking in the data. We deform to deliver how history develops at the surface as well as below it, above it, of it, beyond it. We distort for discovery—the past’s endless arrangements and rearrangements of code and meaning, significance and power, assembling in a process that always breaks down, degrading into signals that were once disorganized yet, as we turn back to them, build up again into new clues, new songs, new messages, new stories.

My deepest thanks to the wonderful students in Digitizing Folk Music History this year for their ideas, contributions, and willingness to let me share their findings with a broader audience. This assignment was developed with ace digital scholarship librarian Josh Honn. Thanks to Matt Taylor and the Multimedia Learning Center (MMLC) at Northwestern as well as the staff at the Northwestern Library Repository and Digital Curation Division for technical support.

Addendum

Here is the assignment for students, along with an additional experiment they do using the paper.js tool.

- In the BFMF Digital Archive or another digital archive, browse and select an image that interests you to download.

- Read all of “Glitching Files for Understanding: Avoiding Screen Essentialism in Three Easy Steps” by Trevor Owens.

- How to change a file extension (on a Mac):

- Go back and follow the steps he took in the “Edit an Image with a Text editor” section using the image you downloaded from the digital archive. Make sure to save each version of the file as you follow the instructions. When you are done you should have (1) the original .jpg file, (2) the post-cut up .jpg file, and (3) the .jpg file after you pasted new information in.

- Do: Feel free to try this on your own computer, but each operating system will react differently to this process. If you have any issues, try visiting the Multimedia Learning Center’s classroom (check to see if it’s available first) and using their computers (we’ve tested this on Mac OS X 10.9.1 and it works).

- Don’t: Do not delete or edit any of the first lines of code in the .txt file (nothing bad will happen, but the experiment won’t work). Scroll down a bit and try deleting, adding, and editing some of the code deeper in the file.

- On the web, go to paper.js, select one of the examples, play around and then select “source in the upper right hand of the screen.” Try and read the code, look for numbers in blue, and experiment by inserting new numbers. Click “run” in the upper right hand corner of the screen and see what”™s changed. Feel free to repeat/go crazy.

- In WordPress, create a new post and upload/insert each of your 3 images.

- Write a one-two paragraph reflection: Might the unlikely concept of “deforming” evidence lead to new historical insights or not? Did you notice anything new or surprising about the object by “deforming” it? What was your experience of playing with javascript in paper.js? What does code allow you to do with objects? Did this make you think about the archival material in a new way?

- Choose blog category.

- Add tags (keywords) to your post.

3 thoughts on “Distorting History (To Make It More Accurate)”